I am still living the life of those times… Theodore Bikel

On October 2, 2014, Israeli anchor Gabi Gazit interviewed Theodore Bikel (1924-2015) on his program at 103FM radio station in the afterglow of Bikel’s ninetieth birthday. The interview was held at the initiative of the Israeli music connoisseur and collector Dudi Patimer. Speaking live from Los Angeles to Tel Aviv, Bikel was nearly offended when Gazit asked him if the interview should be carried out in English or Hebrew. With a distinctive “sabra” accent and in his unmistakably deep baritone voice, Bikel reprimanded Gazit in highbrow modern Hebrew by saying that “the Hebrew language is still holding on my lips”. Towards the end of the interview, when asked if he remembers his early days in Tel Aviv, Bikel responded simply with the epitaph found at the top of this article.

Multifaceted and multidisciplinary artist Theodore Bikel passed away in Los Angeles last July 20. It is proper for the JMRC to celebrate the memory of this remarkable figure, whose merits include, among many artistic achievements, some of the earliest commercial recordings of Israeli and other Jewish folksongs made for the international market after World War II. The Song of the Month is dedicated to Bikel’s recording of ‘Karev yom,’ one of the many Hebrew songs that Bikel performed, recorded and was instrumental in disseminating it internationally.

A lot has been (and will be) written about Bikel. Most obituaries stressed, with a substantial measure of justification, his cosmopolitan persona or his career as an American theatre and movie actor, entertainer, and folk song revivalist. Music reviewers stresses his Yiddish or international repertoire. Bikel made a career out of his cosmopolitanism by assiduously playing the “other” on the stage or on the screen, exploiting his virtuosic capacity to speak, and also to sing, in countless languages.

However, in Bikel’s mind, the Israeli period of his life remained a vivid experiential presence. Bikel lived in Israel, more precisely at 62 Rothschild Avenue in Tel Aviv, from 1938 when he arrived from Vienna with his family as a fourteen-year old refugee, to 1946, when he moved to London to pursue a career as a professional actor at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.

I had the privilege of meeting Bikel at the 2013 season of KlezKanada in the outskirts of Montreal. He was in high spirits, exceptional shape and once again in love. We talked at his initiative (and most of the time in Hebrew) about his Tel Aviv years and how profoundly significant that relatively short period was for his future career. He recalled the names of every personality at the Cameri Theater, of which, in 1944, he was one of the founding actors, as well as of the incipient Israeli music scene.

Bikel’s death was marked in Israel by reserved and mostly short factual obituaries in some leading newspapers as well as on some websites, most especially the one of the Cameri Theatre. Undoubtedly, his leaving Israel in 1946 to pursue his personal career at the peak of the struggle of the Zionist movement to achieve independence in the aftermath of the Holocaust (of which he luckily escaped), tainted him as a kind of deserter. It was a time marked by heroic sacrifice that included surrendering personal ambitions in favor of collective interests. However, Bikel’s Viennese heritage of cosmopolitanism and his artistic ambitions could not find expression in a besieged community bound to a war of survival of uncertain results.

In addition, and in spite of Bikel’s deeply emotional attachment to the formative period of his youth in Tel Aviv, he had, as is well documented, an extremely complex approach to Israel. He often expressed political and social criticism towards Israel and its policies. It took him sixty years to make an emotional comeback to Israel, in order to be honored by the Friends of the Cameri Theatre in Tel Aviv and to reencounter local artists who fondly remembered him from the early 1940s.

The “Israeli” Theodore Bikel must be subjected to a much more detailed analysis than what this short note can allow. Such an analysis must go beyond Bikel as an individual and contextualize him in terms of a generation of Israeli artists who left the country just a few years after the establishment of the state as well as their social networks abroad (e.g. Bikel’s own collaboration with Dov Seltzer and the latter’s wife, singer Geula Gil). We shall therefore dedicate the rest of this note to a few remarks concerning Bikel as a performer of Hebrew songs and restore him to a more dignified position in the narrative of the Israeli Hebrew song. Suffice it to say that the name of Bikel does not appear in the list of performers in Zemereshet, the major website dedicated to the early Hebrew song, even though I found that a few of Bikel’s recordings, such as the song ‘Ada,’ are embedded in this website. I believe that his recordings appear in Zemereshet for a simple reason: there are hardly any other recorded renditions of songs such as ‘Ada.’

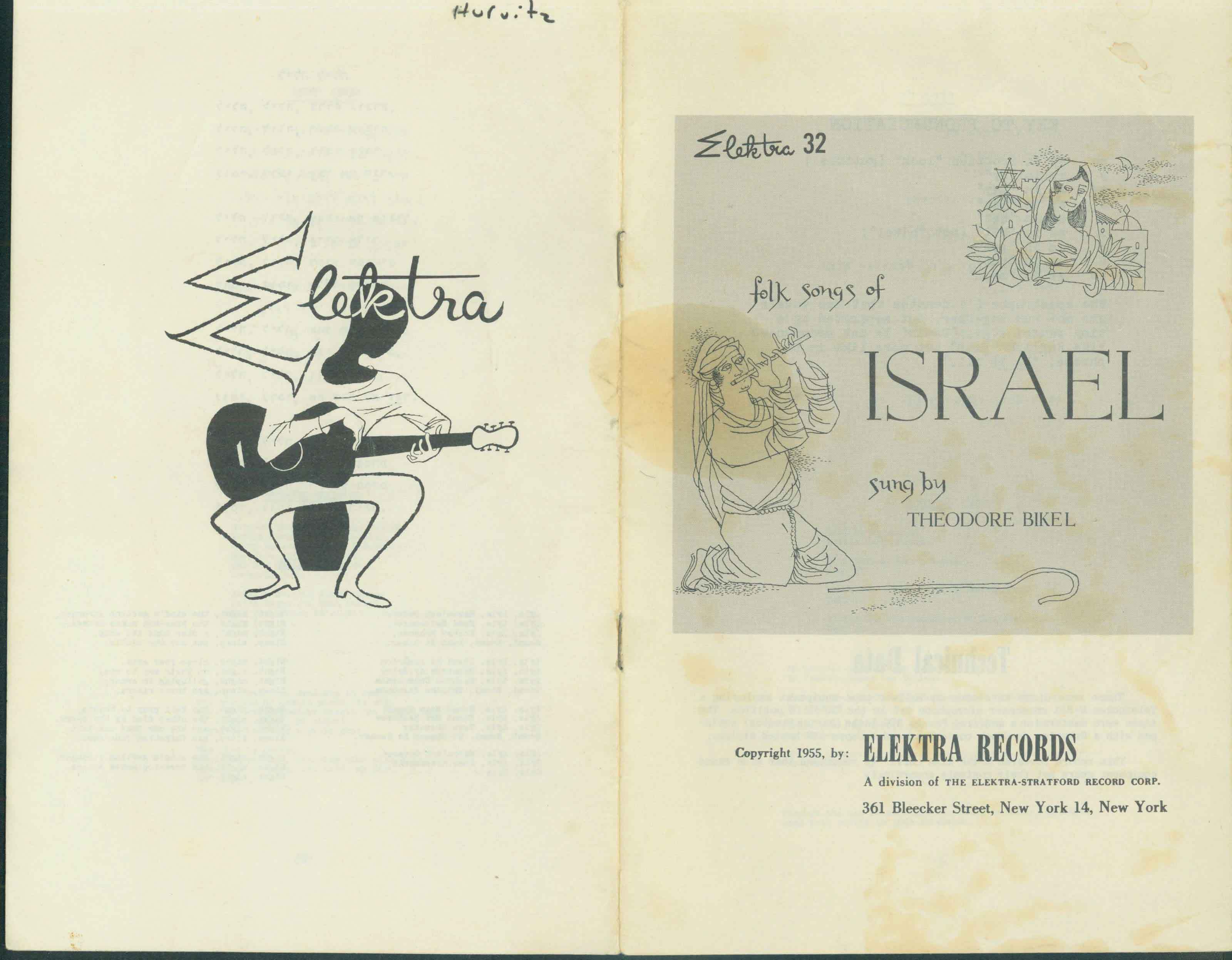

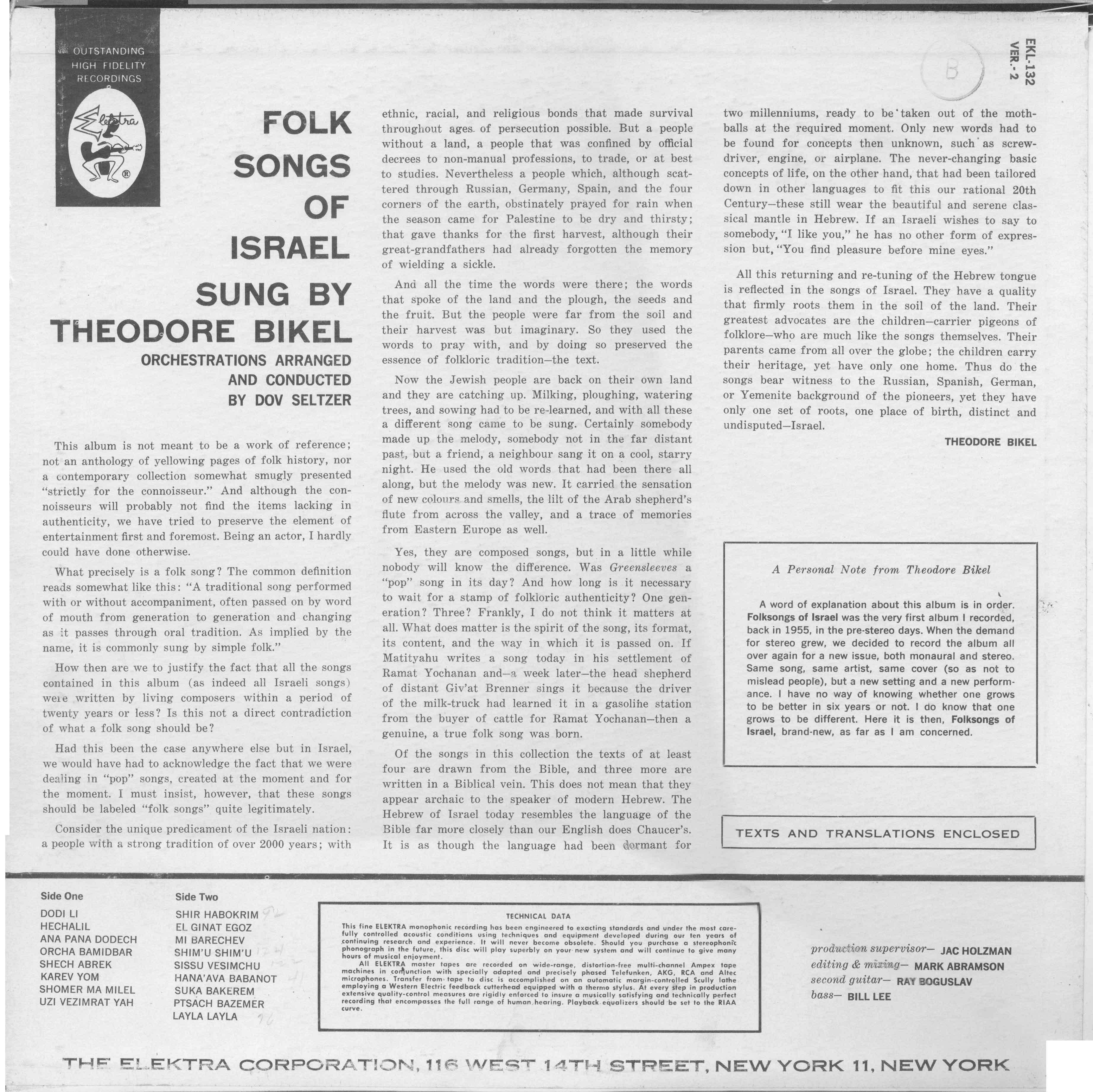

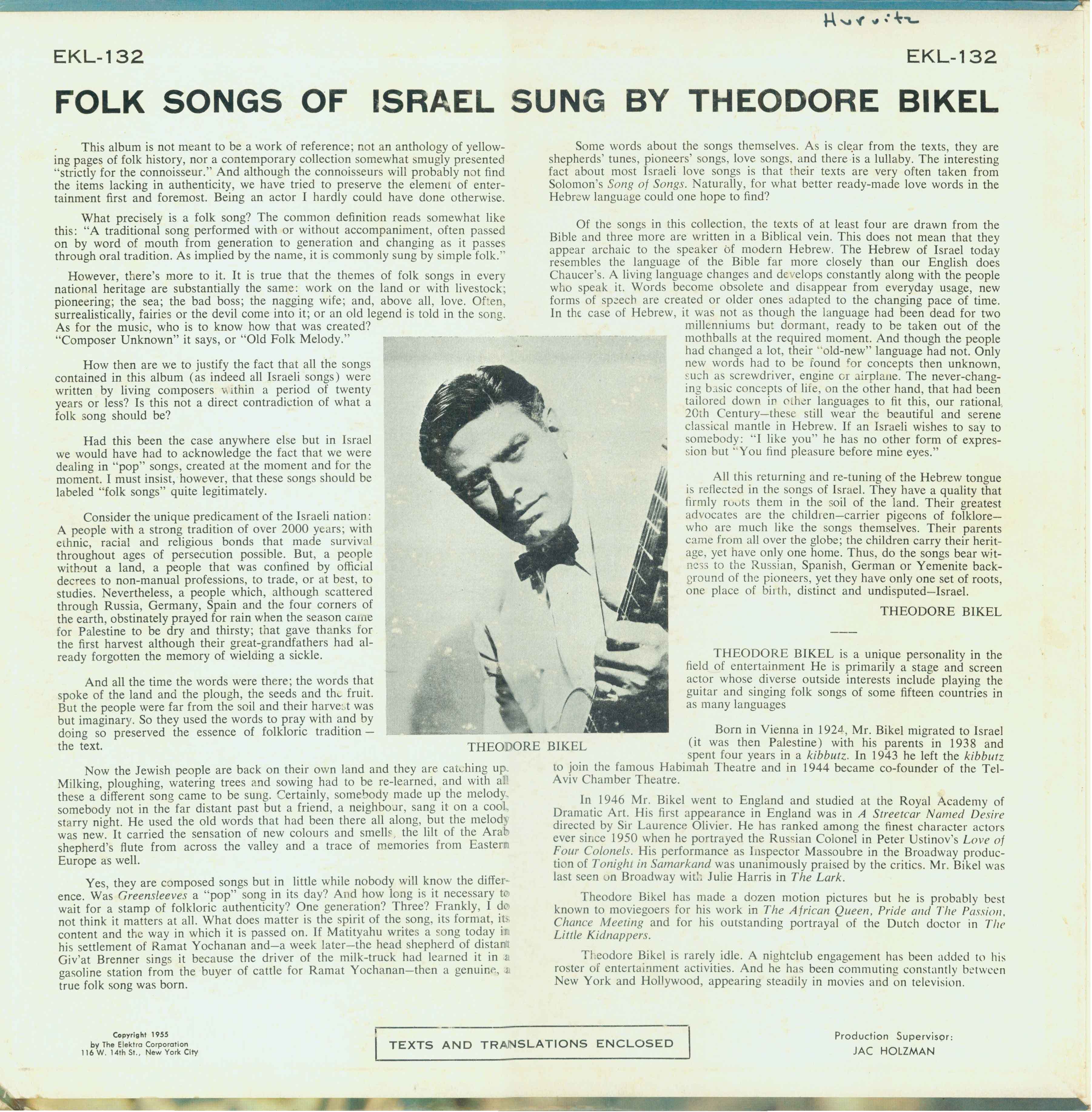

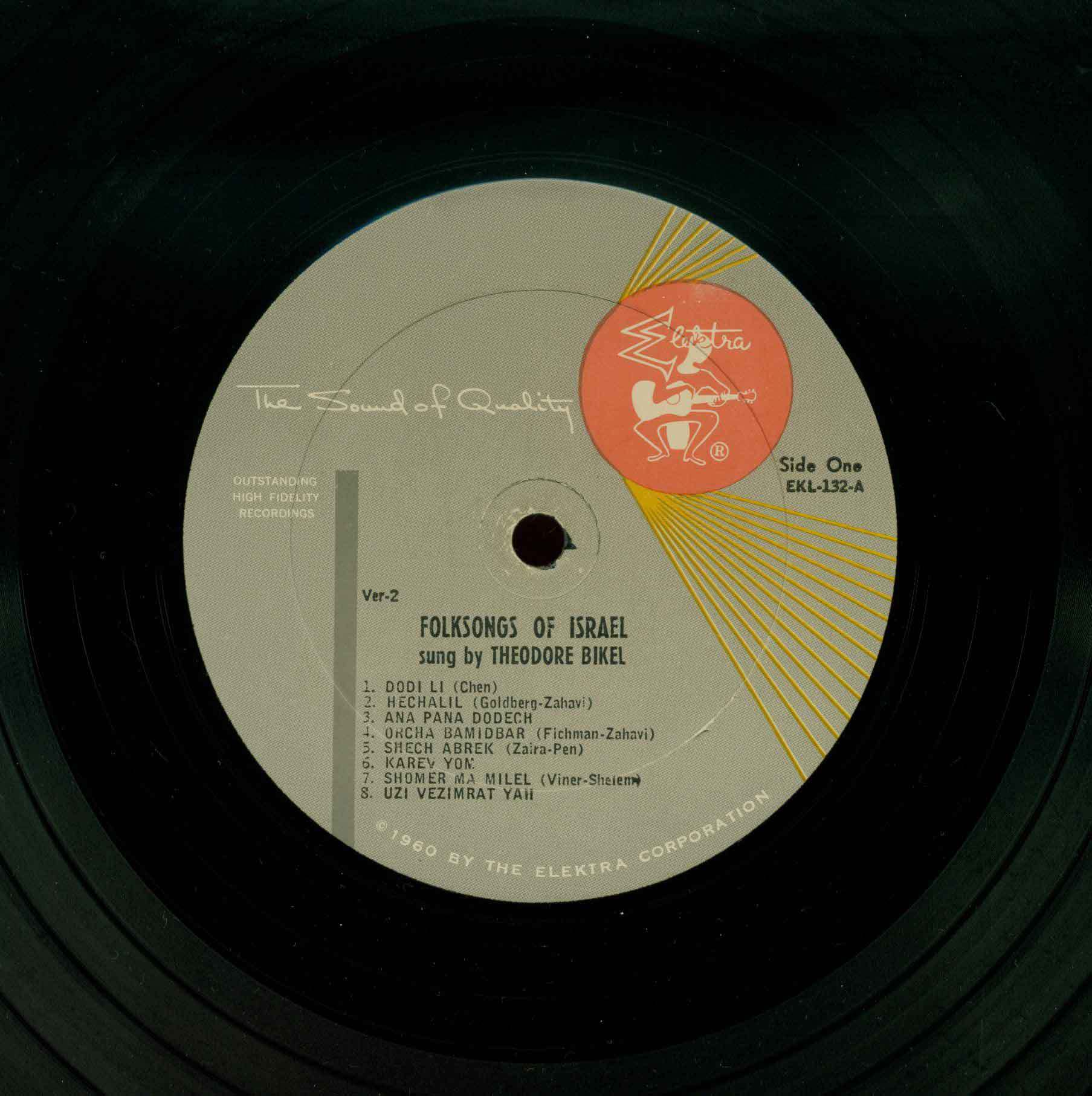

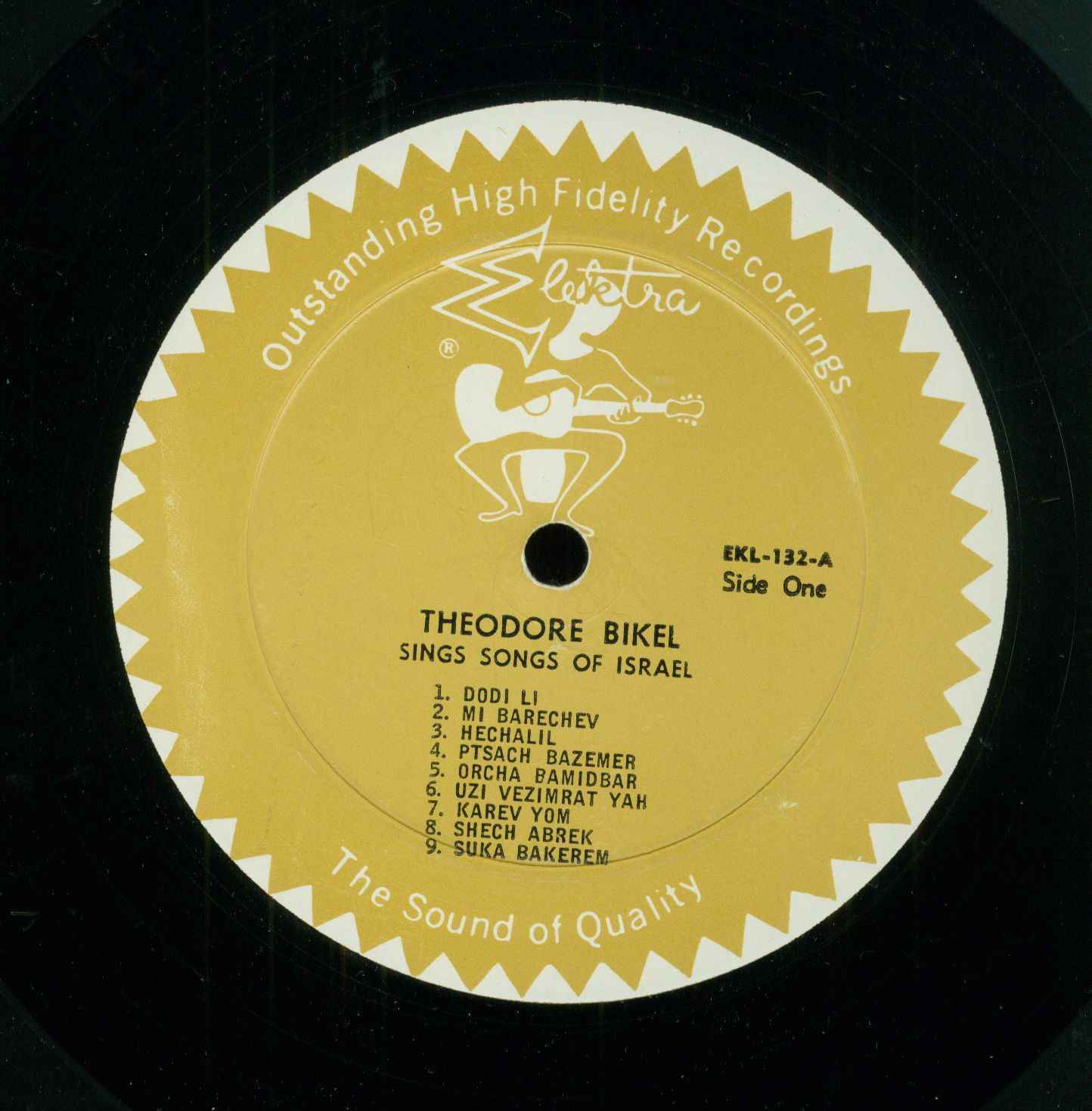

The genesis of Bikel’s career as a professional singer was marked by his first landmark long-play of songs eventually titled Theodore Bikel Sings Songs of Israel. The original version of this record was released as a 10-inch vinyl in 1955 under the title Folk Songs of Israel by Elektra (EKL 32) and rereleased in 1958 (EKL 132, also appeared in France in 1957 as Israel - Chansons Traditionnelles d'Israel, Mode Disques – MDINT 9 179; the 1958 LP was reprinted two more times).[1] Scholars of Israeli music hardly addressed this record in its social and historical context. This obliviousness is part of their general circumvention of the topic of the early reception and recording of the Israeli “folk” song in the USA by venture record companies such as Elektra.[2]

An account of Elektra Records in its crucial years under the leadership of Jac Holzman (b. 1931) from 1950 to 1973, dedicates a sizeable section to the artist that made this company a success to start with, the newcomer (to the USA) Theodore Bikel.[3] Elektra was a small independent folk label when Holzman met Bikel that grew to become a major, multi-faceted, hit-making concern.

We shall quote Holzman verbatim, as he speaks to Mick Houghton: “Folk Songs of Israel really changed my way of thinking. Although the album only credits singer Theodore Bikel in small type, in a little over a year we sold about 15000 copies – a big hit for us. He was a working actor just starting out in America and on Broadway, but he was the pivot point for Elektra: for the first time the artist was as important as the material. That’s when I realized that an artist could carry a folk record, which was a discovery for me.”

“I first met Theo at a typical Village party, where he was passed the guitar…I was struck by just how powerful a singer and performer he was. He could just suck the air out of the room with a blazing performance…. He agreed to come to my little railroad flat, and we taped a few of these songs to see how others would react, because I knew what he can do [in] live [performances]…I knew there was a hunger and an audience…It was a simply and very engaging record to make: just Theo’s voice and his guitar.”

As mentioned above, the album was first released as Folk Songs of Israel in 1955 with Bikel’s name appearing is small letters and with two simple Orientalist pencil drawings in its cover. It was revamped as a 12-inch album titled Theodore Bikel Sings Songs of Israel in 1958 adapting the jacket to the new format and replacing the original cover with a photograph.[4] In Holzman’s words: “[The new cover] pictured a kibbutz girl in the kibbutz uniform and pert hat…her sun-bronzed legs marching happily across a field, with a hoe on her shoulder. Elektra received numerous enquiries asking about the girl and the kibbutz she lived on. In fact she was a model, and the field was in Long Island.” Bikel recalled the same incident in a relatively recent interview.

Houghton concludes his discussion of Bikel’s debut recording as follows: “Holzman had no doubts that Folk Songs of Israel would do well, because there were very few albums of Israel folk songs and there was what he calls “a very big Israeli consciousness in the United States.” Put differently, there was a demand for Israeli “products” in North American concentrations of Jews and Bikel was the right person, at the right time and place. The sound and the packaging of Bikel’s album catered to this Jewish market and its imagination of the new Israel. The suggestive cover of Theodore Bikel Sings Songs of Israel, which now we know is in fact a fake, visualized Israeliness as the target audience wanted to imagine it: a young, hard-working laborer firmly attached to the land, free from the shackles of religious Jewish Orthodoxy and sexually appealing. It recalls and in fact emulates similar graphic designs from record jackets issued in Israel at that same period.

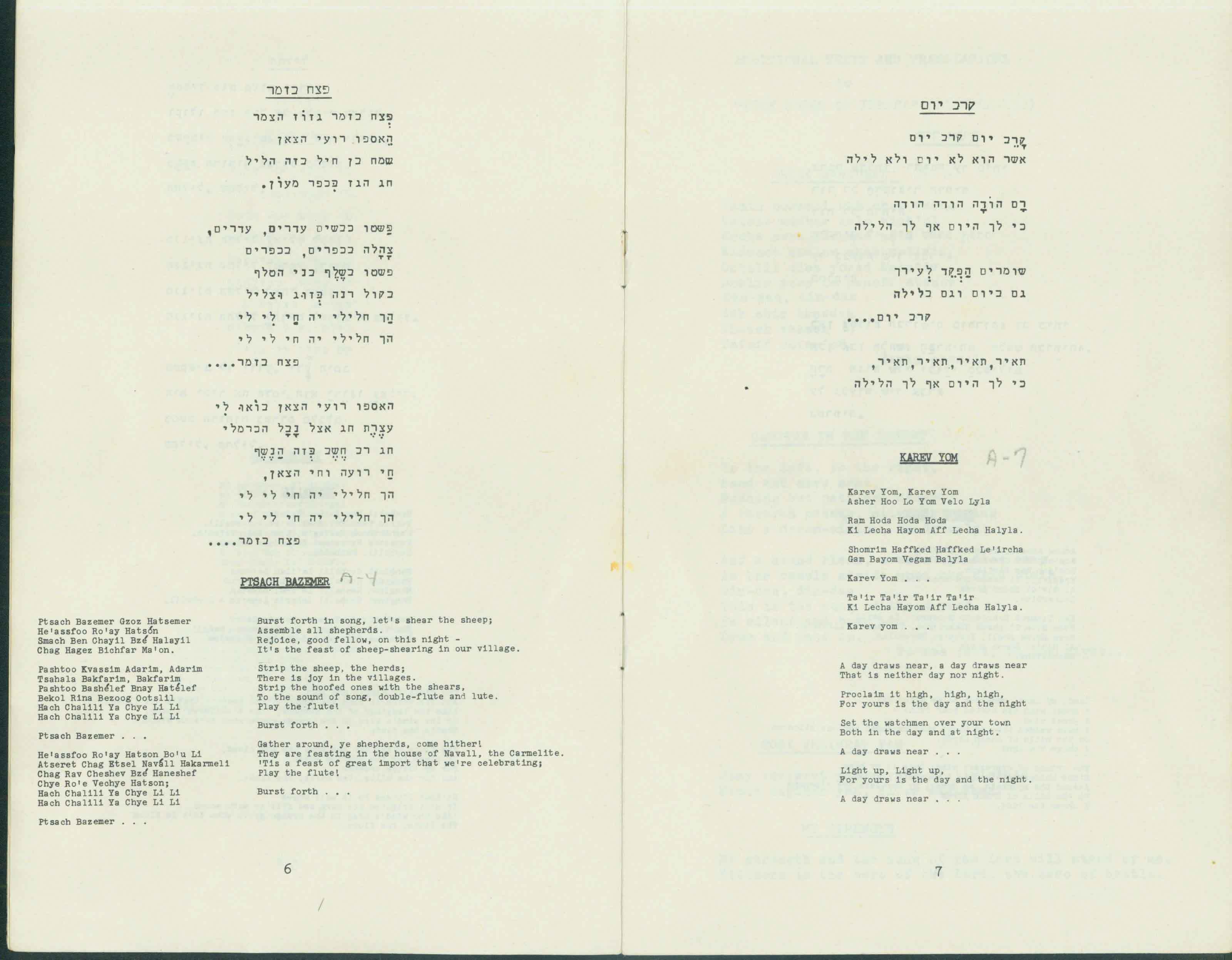

Theodore Bikel Sings Songs of Israel contains eighteen songs averaging two minutes each. The selection of songs on this album (see Appendix) is extremely telling of the period. The absolute majority of the songs (thirteen out of eighteen) are by five canonic Israel composers that dominated the “golden age” of the modern Hebrew song in the 1930s and 1940s: Matitiyahu Shelem (four songs), Emanuel Amiran (three songs), Mordecai Zeira, Amitai Neeman and David Zehavi (two songs each). Two of the songs are by Yemenite-born musicians who were active in the musical scene of British Palestine, Sara Levi-Tanai and Yehiel Adaqi. Only one of the songs is “traditional” (no. 7: ‘Karev yom,’ analyzed below in detail). From the point of view of poetry, the reliance on verses from the Biblical ‘Song of Songs’ (three songs plus the pseudo-Song of Songs text by Amitai Neeman to his ‘Hana’avah ba-vanot’) is characteristic of the early Hebrew repertoire. The rest of the texts are by canonical poets whose poems were set to music by composers of the period, such as Lea Goldberg, Alexander Pen, Natan Alterman, Yaacov Fichman and Yaacov Orland. Several of the texts are by the composers themselves, the most notable case being Matitiyahu Shelem.

Regretfully, we do not possess a very precise record of how Bikel acquired the Hebrew repertoire that he recorded in 1955. Several of these songs were composed after he left Palestine in 1946 for London. Therefore, he probably learned them from the rare early recordings or from contacts with other Israeli singers and musicians arriving periodically to the USA, most probable from the arranger of his own LP, Dov Seltzer (see more below). It is remarkable that most of the songs that Bikel sings on his record were performed and recorded (at times in the USA) at about the same time by female singers, the absolute majority of whom were of Yemenite-Jewish origins (Hanna Aharoni, Ahuva Tzadok, Naomi Tzuri, and Shoshana Damari).

In spite of the marketing of the record as Bikel’s solo album his voice is doubled by a second one on several items. This is the voice of Raphael (Ray) Boguslav (1929-2010), who is listed as “second guitar”. A graphic designer, Boguslav was active in the folk music scene in New York in the 1950s. In addition, a darbukka accompanies Bikel is some songs but the credits in the record do not list the name of the player. Another musician, Bill Lee, is listed in the record jacket as “bass.” Lee is none other than William James Edwards 'Bill' Lee III (b. July 23, 1928) an accomplished musician who accompanied many folk music artists of the 1950s and 1960s, among them Bob Dylan.

The texture of Bikel’s LP slightly predates the style of the duos and trios of Israeli singers that became so popular in the late 1950s and early 1960s, especially the Trio Arava, that Duda’im (who also recorded for Elektra) and later on the Parvarim. This “orchestration” is the work of the (at that time) young Romanian Israeli musician and eventually Israeli Prize Laureate (2009), Dov (Dubi) Seltzer (b. 1932). Seltzer was in the early 1950s a student at the Mannes School of Music with an already remarkable musical career in Israel following his immigration in 1948. As a key founding figure of Lehakat Hanahal, a mythical Israeli army ensemble, Seltzer was probably a major resource for Bikel’s repertoire and production. Bikel’s earlier rendition of the Goldberg/Zehavi song ‘Hechalil’ bears the “hand” of Dov Seltzer and a strong resemblance to the one by the Dud’aim, recorded in 1958.

Finally, one must mention another characteristic of Bikel’s delivery, his noticeable pronunciation of the Hebrew language, especially of the consonant “resh” and some of the guttural letters. It appears that he wanted to bypass his German accent and sound as “sabra” as possible.

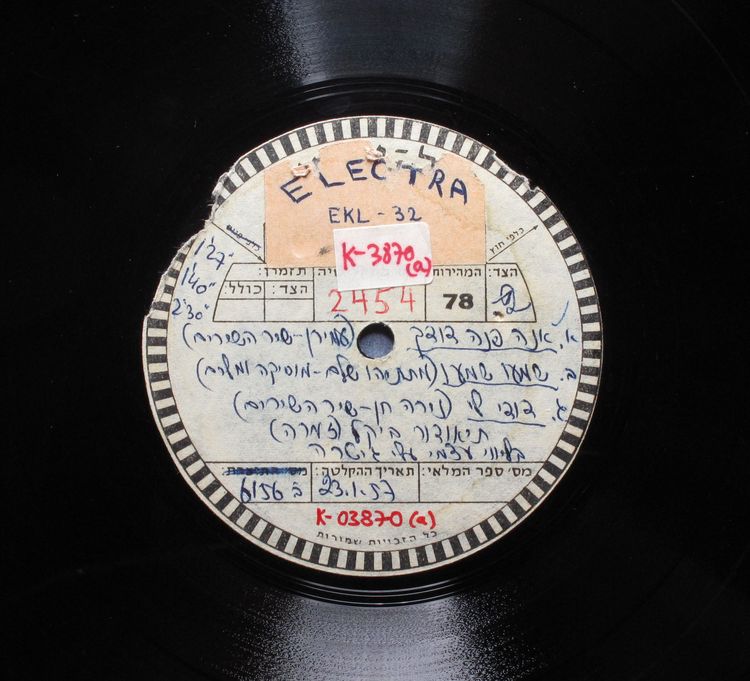

A significant historical detail has to be noticed in terms of Bikel’s early reception in Israel. The archive of the Israel Radio (Kol Israel; now housed at the National Sound Archives) holds broadcast records dating from 1957that include copies of several of Bikel’s songs. This means that the Israeli radio acquired a copy of the early Folk Songs of Israel (1955) and broadcast some of the songs. Many young Israeli artists then making their first steps in their careers heard these songs. From these records we learn that Bikel’s voice was featured on the Israeli radio, then a total governmental monopoly, in 1957 in spite of his status as “yored” (“[one who] descended” in the sense of an Israeli who left the country for good).

One of the unique items in Bikel’s record is the song ‘Karev yom’. This is the only song belonging to the traditional Jewish repertoire, i.e. from the Diaspora experience rather than from the emerging triumphalist Israeli Hebrew culture. The song belongs to the Ashkenazi repertoire for the Passover Seder, the festive meal accompanied by the ritual reading of the Haggadah. It is the last stanza of the alphabetical piyyut whose refrain is ‘Uvkhen vayehi be-hatzi ha-layla’ by Yannai (Palestine, sixth-seventh century CE). Originally, it belongs to the triennial order of reading of the Torah practiced by the Jews of Palestine during the Byzantine period. It corresponds to a series of seven poems for the Sabbath in which Exodus 12, 29 (“At midnight the Lord struck down all the firstborn in Egypt, from the firstborn of Pharaoh, who sat on the throne, to the firstborn of the prisoner, who was in the dungeon, and the firstborn of all the livestock as well.”) is read. You can read more about this text in Rabbi Peretz Rodman’s site.

This piyyut emerged into the Ashkenazi Haggadah several centuries later, most probably transmitted via Italy. According to Joshua Kulp, it was originally performed as a krovah for Shabbat HaGadol, the Sabbath preceding Passover (see Mahzor Vitry, Ms. Parma, Biblioteca Palatina, no. 2574, fol. 228). This piyyut already appears as a Passover song in the so-called Pratto Haggadah from the fourteenth century (Ms. JTS 9478).

When and where was the last stanza of Yannai’s ancient piyyut set to a special melody is for the moment unknown. The present musical setting however provided it with a modern existence as an independent song. This melody was widespread in Israel, and even entered the modernized Haggadot of several kibbutzim. Several Israeli popular artists, such as Yaffa Yarkoni and Shuli Natan, performed and recorded this Passover song. Its Israelization was such that is also acquired a choreography becoming also an Israeli folk dance.

A musical notation of ‘Karev yom’ appears in the anthology of “Israeli” liturgical music edited by Meir Shim’on Geshuri (Ḳol Yisraʼel: Anṭologyah Yisreʼelit-Mesoratit La-Ḥazanut Shel Kol Ha-Shanah. Tel-Aviv: Bet-ha-keneset le-noʻar ule-talmide Be.ha-s. 'Bilu' ṿeha-Seminar le-limude ha-Yahadut 'Selah', vol. 1, 1964, p.206). The melody is attributed there and in various other sources to the Bratslav Hassidim. However, as with all the ascriptions of niggunim to a specific dynasty or rebbe, there is no empirical way to prove or deny such assertions.

Moreover, this melody was not documented in musical notation earlier on. For example, a 1938 Haggadah printed in Tel Aviv by Jacob Smilansky contains a substantial musical appendix prepared by the composer Eliyahu David Jacobsohn (1881-1961) from versions sang by cantor Shlomo Ravitz, at that time the chief cantor of the Great Synagogue in Tel Aviv. The music provided by Ravitz for our piyyut is set to the first stanza, not to the last one (‘Karev yom’) and it is a rhythmical rendition of the traditional Ashkenazi nussah for the recitation of the Haggadah. A similar version to Ravitz’s appears in the Haggadah Eretz Israelit (Tel Aviv: Sinai, 1950, p. 36), one of the earliest “patriotic” Israeli Haggadot. Also Haggadot with musical notation published in Europe and the USA since the late nineteenth century do not contain a melody for ‘Karev yom.’

If such a popular melody for ‘Karev yom’ existed then in Israel, would a cantor of the stature of Ravitz not register it? Or does Ravitz’s old Ashkenazi melody, recorded in the National Sound Archives by various German and Swiss informants, reflects a non-Hassidic Ashkenazi tradition that frowns upon rhythmic melodies of the kind of the “common” ‘Karev yom’? Considering the Israeli trajectory of this specific niggun for ‘Karev yom’,[5] is it conceivable that one of the composers of the Passover Seder from a kibbutz matched a melody borrowed from some unknown Hassidic source (or even from oral tradition) to the text of ‘Karev yom.’

The melody is a two-section niggun. Each section alternates between the verses in the poem. The first section is in minor and explores the lower register in a narrow range of a fifth. The second section contrasts with the first in its intensity: it moves up to a slightly higher register touching the sixth degree and modulates to the “Ukrainian” or “altered” Dorian mode (with the raised fourth that creates an augmented second between the third and fourth degrees of the mode).

The text in the piyyut is:

קָרֵב יוֹם אֲשֶׁר הוּא לֹא יוֹם וְלֹא לַיְלָה

רָם הוֹדַע כִּי לְךָ הַיּוֹם אַף לְךָ הַלַּיְלָה

שׁוֹמְרִים הַפְקֵד לְעִירְךָ כָּל הַיּוֹם וְכָל הַלַּיְלָה

תָּאִיר כְּאוֹר יוֹם חֶשְׁכַת לַיְלָה

The performed version adds many word repetitions, as follows:

קָרֵב יוֹם, קָרֵב יוֹם

אֲשֶׁר הוּא לֹא יוֹם וְלֹא לַיְלָה

רָם הוֹדַע, הוֹדַע, הוֹדַע

כִּי לְךָ יוֹם אַף לְךָ לַיְלָה

שׁוֹמְרִים הַפְקֵד, הַפְקֵד לְעִירְךָ

כָּל הַיּוֹם וְכָל הַלַּיְלָה

תָּאִיר, תָּאִיר, תָּאִיר, תָּאִיר

כְּאוֹר יוֹם חֶשְׁכַת לַיְלָה

Here is the translation by Joshua Kulp from The Schechter Haggadah: Art, History and Commentary (Jerusalem, 2009):

Draw near the day which is neither day nor night;

Exalted One, proclaim that Yours are day and night;

Set guards over Your city all day and night;

Brighten as day the darkness of the night;

And it came to pass at midnight!

As hinted above, Bikel transforms this religious poem into an unassuming folk song liberated from any gratuitous pathos. His performance is slightly faster and smoother than most other recordings, certainly in comparison to contemporary recordings by synagogue cantors such as hazzan Efraim Di Zahav (Goldstein) who recorded it in 1956. A performance of this piyyut similar to Bikel’s is the one by the renowned Israeli actor Hanna Rovina (1893-1980) that was recorded by the Israeli TV in 1980, just months before she passed away. In spite of the traditional Passover Seder table choreography, Rovina interprets the song responsorially with an unusual and yet restrained intensity, recalling the performances of Russian folksongs. Indeed the musician Aharon Shefi vividly remembers Rovina performing the song in this style during the Habimah Theatre’s tours throughout Israel in the 1950s. Maybe Bikel heard the song from Rovina during his formative years at Habimah (1942-1944)?

Appendix – Contents of Theodore Bikel Sings Songs of Israel and brief remarks

- Dodi Li (Song of Songs, Nira Chen, set for a folk dance)

- Mi Barechev (Rafael Saporta, Emanuel Amiran, recorded early by Shoshana Gamlielit-Lavi, aka Shoshik Shani [1928-2011], NSA, K04902)

- Hechalil (Lea Goldberg, David Zehavi, composed c. 1953?, made famous by the 1958 recording of the duo, Ha-Duda’im, perhaps under the influence of Bikel’s interpretation)

- Ptsach [!] Bazemer (Matitiyahu Shelem, recorded early by Ahuva Tzadok)

- Orcha Bamidbar (Yaacov Fichman, David Zehavi, composed in 1927 recorded in 1955 by Shoshana Damari, and one year after by the Arava Trio)

- Uzi Vezimrat Yah (Psalm 118, 14 and Psalm 24,8, Yehiel Adaqi, composed in the 1930s, set to a folk dance by Rivka Sturman, recorded by the Yemenite-born singer Naomi Tzuri,)

- Karev Yom (From the Passover Haggadha, Hassidic tune)

- [‘Al Geva’ot] Shech Abrek (Alexander Pen, Mordecai Zeira, composed in 1941)

- Suka Bakerem (Aharon Feldman, Emanuel Amiran, the only recording in Zemereshet of this song is the one by Bikel),

- Sissu Vesimchu (Matitiyahu Shelem, composed before 1951, first recorded by the Choir of Kol Tziyyon la-Gola in 1951; Bikel’s recording is much more faster)

- El Ginat Egoz (Song of Songs, Sara Levi-Tanai, recorded early by Hanna Aharoni with the Emanuel Zamir Ensemble)

- Shir Habokrim (Yaacov Orland, Mordecai Olri-Nozik, composed 1953)

- Shomer Ma Mileil (Matitiyahu Shelem, composed 1940, recorded in the 1950s by Vera Roger-Waters)

- Hana’ava Babanot (Amitai Neeman recorded by Ahuva Tzadok in 1955 in her album Israeli Folk Dances, set of course to a folk dance)

- Ana Pana [sic; should be Ana Halakh] Dodekh (Song of Songs, Emanuel Amiran)

- Shim’u Shim’u (Matitiyahu Shelem, composed in 1940, for dance for the Omer ceremony in kibbutz Ramat Yokhanan)

- Ada (Arik Lavi, Amitai Neeman, composed in 1948 recorded by Sharon Aharon)

- Layla Layla (Natan Alterman, Mordecai Zeira, composed in 1946, recorded by Shoshana Damari)

[1] Not only the cover photograph changed but also Bikel expanded in the third and fourth reprints the text that appears in the back of the record jacket. In the fourth reprint, a biography of Bikel was also added. Bikel’s text is extremely interest but a discussion of it is beyond the scope of this short article.

[2] Bikel recorded a second long-play of Israeli songs for Elektra titled A Harvest of Israeli Folk Songs (1961, ELK 210). During the late 1950s and early 1960s Elektra recorded various Israeli artists trying to enter the American (Jewish) market, such as Ran and Nama, Geula Gil and the Duda’im. Elektra was by no means the only producer of Israeli folksongs in the USA during those years.

[3] Mick Houghton, Becoming Elektra: The True Story of Jac Holzman's Visionary Record Label. London: Jawbone, 2010, see esp. pp. 73-75.

[4] I acknowledge here my colleagues at the Dartmouth College Jewish Sound Archive for making available to me the scanning of the records by Bikel discussed in this paper.

[5] There are additional Hassidic niggunim for this text, e.g. one of Hassidut Belz. Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach performs a tune that is similar in structure to Bikel’s version but lacks the modulation in the second section. The Boyan and Viznitz Hassidim in Israel also sing as Carlebach does. Another close version to the ”regular” ‘Karev yom,’ attributed to none other than the initiator of Hassidism Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov (Besht) is performed by the Rebbe of Boston, R. Levy Itzhak Horwitz ben Pinchas David in the recording NSA 2890 (recorded by Avigdor Herzog, August 15, 1987). The Israeli singer Evyatar Banai revived this version in a modern arrangement. See also, Songs of the Chassidim: An anthology, compiled, edited, and arranged by Velvel Pasternak. New York: Bloch Pub. Co., 1968, p. 148.