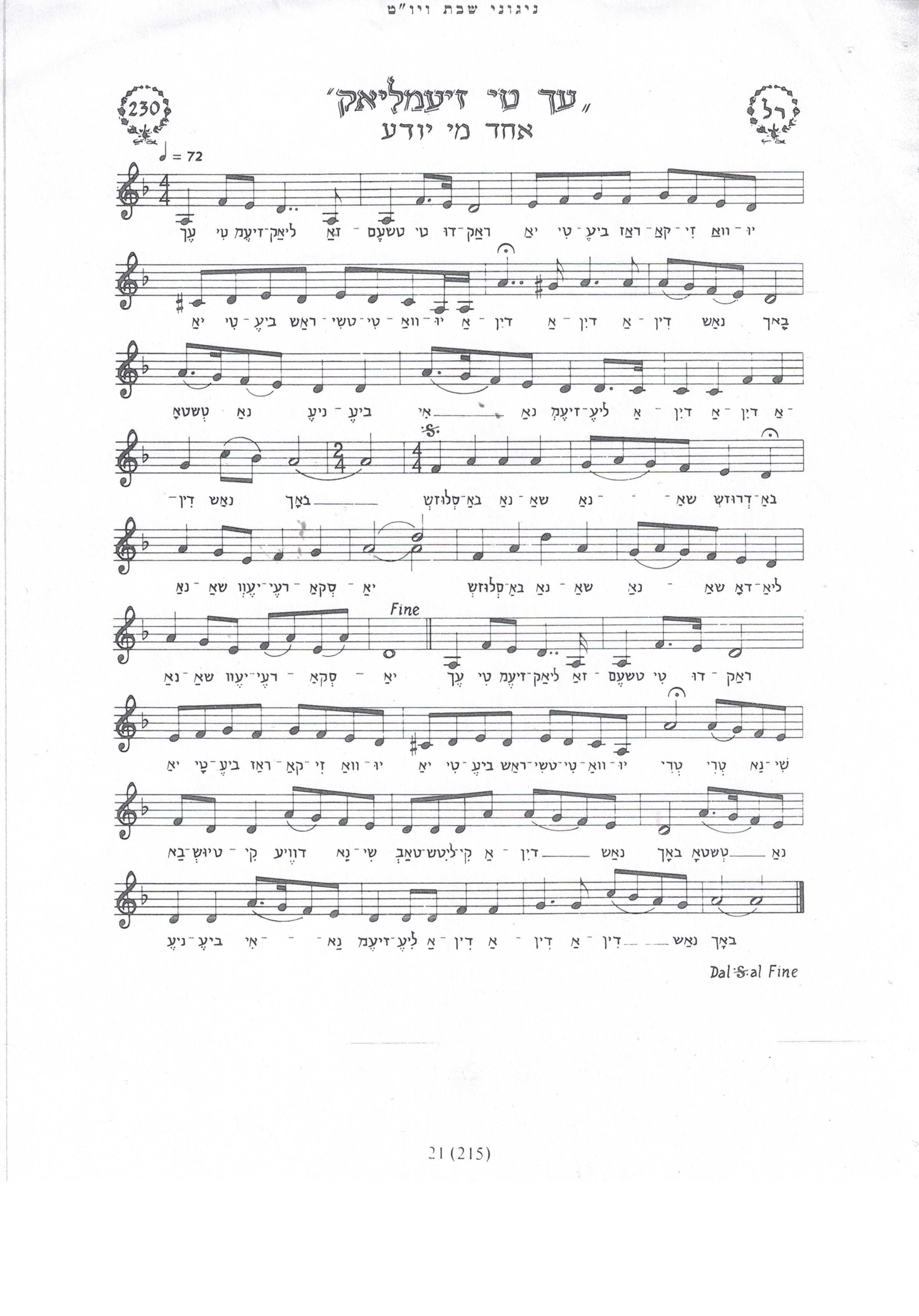

The Thessaloniki version of "Ehad mi yodea." This version was part of a 1982 radio broadcast hosted by Dr. Susana Weich-Shahak. Here she introduces the songs, plays a recording of the introductory blessing and sings all 13 stanza along with a group of singers. Recording taken from NLI YC 01925.

Ehad mi Yodea - Its sources, variations, and parodies

Celebrating Passover, the Song of the Month is dedicated to “Ehad mi yodea” the famous serial folksong added to the Passover haggadah. This article, following the extant substantial scholarship on this subject, will focus on the history of this song within the haggadah, the question of its origins and source, and will examine a few versions and adaptions focusing on changes introduced to the text and the music within different historical contexts and local Jewish traditions.

“Ehad mi yodea” is a cumulative song. An additional line is added to each stanza of the song followed by all previous lines. In this song, each stanza adds a line than opens with a number, usually from one until thirteen. Each number is given a symbolic meaning that is connected to Biblical figures, concepts, and objects related to Judaism: One – God; two – the two tablets of the covenant; three – the Jewish patriarchs; four – the Jewish matriarchs; five – the five books of Moses; six – the books of the Mishna; seven – the days of the week; eight – the days or circumcision; nine – the months of pregnancy; ten – the ten commandments; eleven – stars (from Joseph's dream in the book of Genesis); twelve – the tribes of Israel; thirteen – attributes of mercy (according to Maimonides).

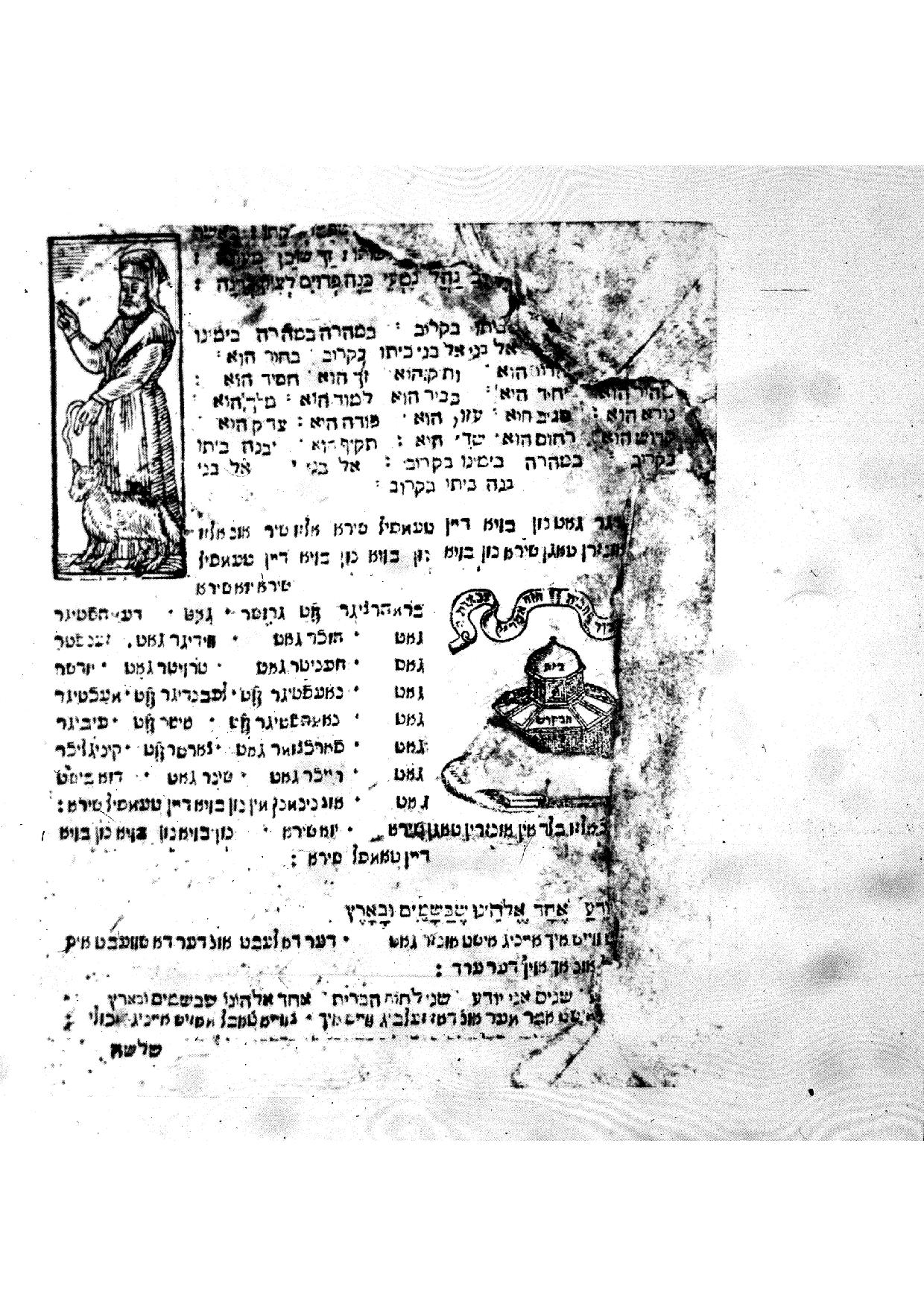

The song is performed at the end of the Passover seder, generally by all the participants right before “Had gadya”, also a cumulative song. “Ehad mi yodea” appears, apparently for the first time, as a manuscript addition (Hebrew and Yiddish) to a copy of the Ashkenazi haggadah printed in Prague in 1526/7 found at the National Library of Israel. It appeared in print for the first time in the 1590 Prague Haggadah. After it was printed it became a fixed component of the Ashkenazi seder. In the first publications, the text of “Ehad mi yodea”, like those of “Had gadya” and “Addir hu,” was published in Hebrew (with a few Aramaic words) along with a translation into Yiddish. One defining characteristic of the Yiddish translations that differs from the Hebrew version is found in the opening line “Der do lebt un der do schwebt,” meaning there God dwells in heaven and there he floats. This specific wording appeared also in German versions of the song (for a detailed discussion of the German variants see Bohlman and Holtzafpel 2001, no. 10, pp. 68-74), and led some researchers to wonder if this is the original formulation of the opening instead of the didactic question that opens the present-day Hebrew version, “One, who knows?” The Yiddish-German formula of the opening line reappears later in some Yiddish adaptations and parodies of “Ehad mi yodea” that will be discussed below.

Questions of origins

The source of “Ehad mi yodea” has been the topic of much scholarly debate and it seems that while there is much speculation, there is little certainty as to its origins. There are two main areas of contention among scholars regarding the source of the song: 1) Whether it is originally a Jewish or a non-Jewish song adapted by Jews; 2) If it is of Jewish origin, did it originated in Ashkenaz or in an Eastern Jewish tradition.

Much of the relevant literature surrounding these two questions has been adequately summarized by Menachem Tzvi Fox (1988) and Joseph Tabory (2008). Fox, for example, theorizes that some of the sources of the meanings of the numbers can be found in Midrash Shmuel. He also claims that the earliest documentation of “Ehad mi yodea” is from a now lost 1406 parchment found in the Worms genizah. This finding points to the Ashkenazi origins of the song as all other versions were documented much later. Research has also explored similar serial patterns of question and answer counting songs in other traditions, such as Muslim, Latin, German, and English in order to establish what the essential parameters of the poetic structure are in order to find out a possible source. While some of these non-Jewish songs predate the 1526 Prague Haggadah, their structure, in the opinion of some scholars, is not always close enough to “Ehad mi yodea” to claim a necessary association between them.

Other versions, such as the German songs Die zwoelf heiligen Zahlen and O Lector lectorum follow a similar structure of questions and answers and its numbers are nearly identical to those in “Ehad mi yodea,” with some of the symbolic meaning of the numbers being more Christian in character. They also feature the distinctive phrasing of God dwelling and floating in the heavens and on the earth. These features led some researchers to question whether the Jewish “Ehad mi yodea” was an adaptation of one of these German songs or the opposite, whether the non-Jewish German songs are paraphrases of “Ehad mi yodea.” One cannot fail to notice that these German songs were first published after the 1590 Prague Haggadah.

In conclusion, despite the many theories on the origins and sources of our song there is no definite answer. This point is best summarized by Tabory: “The outcome of it all is that the idea of a number riddle of this sort appears in many communities and it is usually difficult, if not impossible, to determine the directions of influence.” (Tabory, 1988: 66)

Variations from Sephardic and Eastern Jewish communities

“Ehad mi yodea” began to appear in non-Ashkenazi haggadot only during the nineteenth century. While the Ashkenazi version of the text printed in the haggadah has remained constant, a few folk, parody, Hassidic, and satirical versions in Yiddish and in Russian appeared in the Eastern European communities. The non-Ashkenazi versions, on the other hand, were much more subject to change in their lyrical content. The Judeo-Spanish (Ladino) version, for example, has a few variations.

Shimon Sharvit (2012) pointed out a few variants found in different Sephardic communities. The primary differences between each version, besides melody, is the symbolic attribute of each number as well as the actual amount of numbers. The latter fluctuates between ten in Southern France and fourteen in one version from Majorca.

The Thessaloniki version in Ladino, for example, includes a unique introductory segment “God in Heavens, He will send us to Jerusalem in a large caravan. Who knows One? One is the Creator. Blessed be His name.” Also the attributes of the numbers are different in this version in comparison to the standard Hebrew/Aramaic text, as follows: two are Moses and Aaron (rather that the tablets of the covenant), four are the matriarchs of Israel (rather than just “the matriarchs”), six are the days of the week without the Sabbath (rather that the orders of the Mishnah), seven are the days of the week including the Sabbath (rather than plainly “the days of the week”), eight are the days of the huppah (the wedding celebrations, instead of the days from the birth to the circumcision), eleven are the brothers (sons of Jacob) without Joseph (instead of the stars), twelve are the brothers with Joseph (instead of the twelve tribes), and thirteen are the brothers (sons of Jacob) with Dinah (instead of the measures of mercy). In the attached recording [Example 1], one can hear the Thessaloniki version, which is preceded by explanatory remarks by JMRC scholar and international expert on the Ladino song, Dr. Susana Weich-Shahak.

The lyrical changes found in these versions as well as in versions from places such as Cochin (in Kerala, India) caused some scholars to speculate that the Eastern versions are the original source of “Ehad mi yodea” that were later adopted by Ashkenazi Jews. Sharvit (1972) claimed that since the Eastern versions had twelve rather than thirteen stanzas, those were most likely the original stanzas since he saw no reason why if the original had thirteen stanzas, they would omit the final one. He then assumed that the Europeans added a thirteenth stanza in order to differentiate their song from the ones from the surrounding cultures because the number thirteen is considered to be an unlucky one in Christian societies. This assumption was quickly refuted by A.B. Habermann (1973) who claimed that it was unfounded. Habermann suggested that the reason for the differences between the Eastern and the European versions was mistakes in the oral transmission between European Jews, possibly from Amsterdam, and by the transcribers from the Eastern communities who might have heard the song from an Ashkenazi Jew. Fox’s hypothesis is that “Ehad mi yodea” originated in Ashkenazi communities in the 13th century and arrived to the Sephardic communities in the Iberian Peninsula through Ashkenazi exiles, such as Rabbi Asher ben Yehiel, who fled the Rhein valley following the late thirteenth century persecutions and settled eventually in Toledo, Spain.

Ashkenazi variants of “Ehad mi yodea”

In Eastern European Jewish culture the model of “Ehad mi yodea” has been the basis for several songs in different languages. Hereby follow some examples.

Habad Hasidism

The Habad Hasidim sing a version of “Ehad mi yodea” in Russian called “Ekh ti zimliak,” [Example 2] meaning “Hey neighbor.” Here, the introductory question is different from the canonized Hebrew/Aramaic version. In fact, it is hardly a question but rather a statement: “Hey neighbor, what is with you, fool, let me tell you, let me calculate for you, we only have one God in heaven and on earth, we have one God.”

There are a few available traditional Habad performances of this version. As can be heard in one version sung before the Lubavitcher Rebbe, a soloist begins the song and is quickly joined by the entire audience. As the niggun progresses, it grows in intensity as the tempo increases and the crowd sings louder and harsher. The Israeli klezmer band Oy Division included their take of this Habad version on Dicunt, their 2013 collaborative album with Russian singer Psoy Korolenko. Here, they adapt the song to the klezmer medium with accordion, clarinet, violin and double bass accompanying the singing. They only sing up to the number five and towards the end there is an instrumental break where they play melody without text.

Habad Hasidim and the Lubavitcher Rebbe singing “Ekh ti zimliak”

Modern composer, pedagogue and scholar, Andre Hajdu, arranged “Ekh ti zimliak” for four-hands piano in 1975 and then in 2009 for piano and vocals. In the former, instrumental version, the melody goes back and forth between the two pianists as they interchangeably play and embellish it. The latter version was released by the JMRC on the album Kulmus HaNefesh. [Example 3]

Recent performance of Andre Hajdu's version of 'Ekh ti zimliak' for four hands

Yiddish Folk Versions

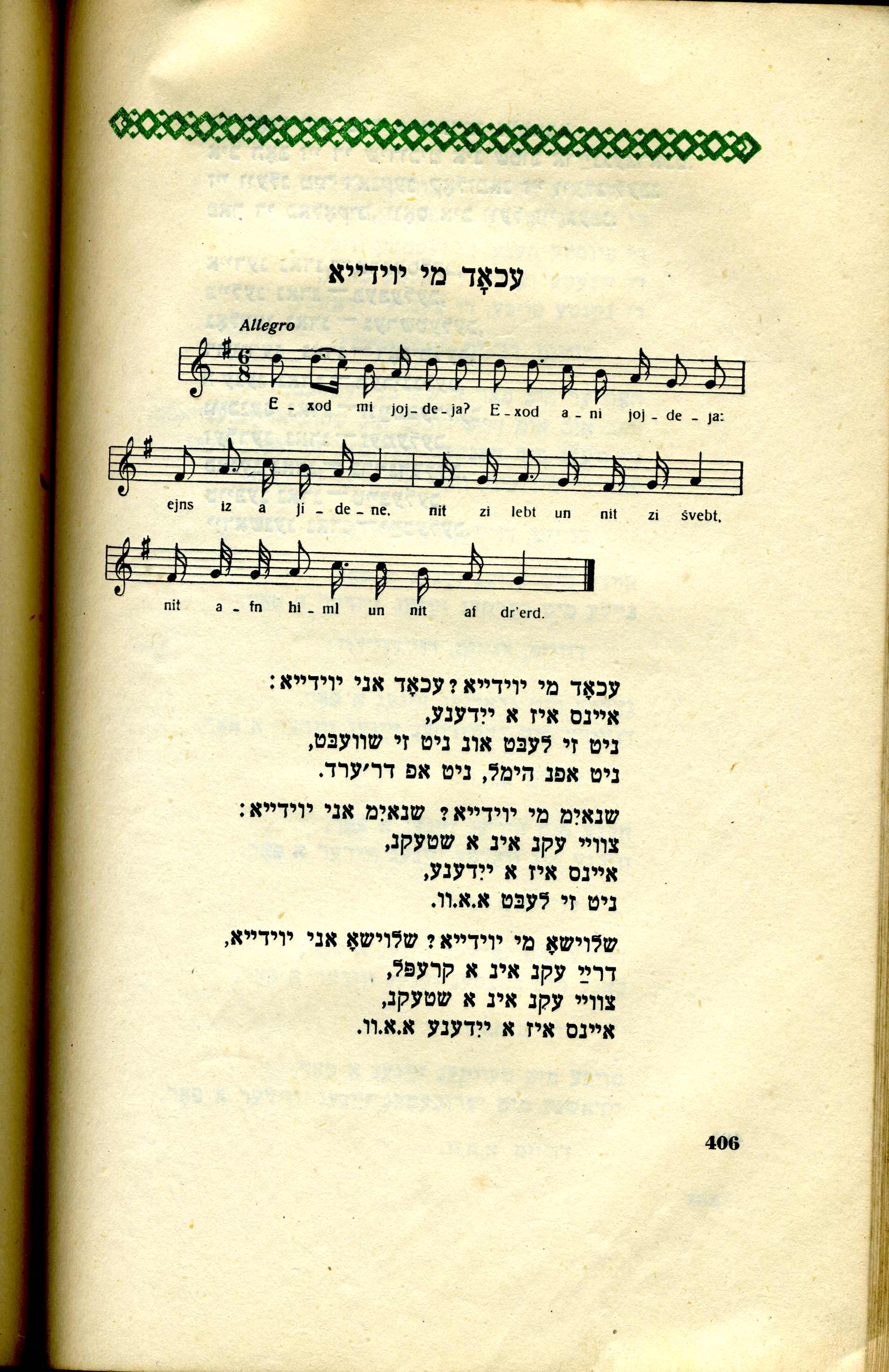

Yiddish translations and paraphrases of “Ehad mi yodea” are usually sung as folk songs and not during the seder. One version that is mostly a faithful translation of the familiar, canonized Hebrew/Aramaic text begins “Hey, hey wise Jews, who is wise about all things, wise wise of all things, tonight please tell tell, please tell us what is One?” The answer that follows is similar to the original Yiddish translation found in the sixteenth century Prague haggadot mentioned above. It refers to God dwelling and floating in heaven and on Earth (“Der, vos lebt, un der, vos Schwebt”).

An additional and well known version is “Mu Asapru,” which is also a translation of “Ehad mi yodea” with a different phrasing in the introduction (“What can I tell what can I say, who knows the meaning of one?”; there is a similar Ladino version that opens “He who knows and he who understands will praise God who is One?”; see Cancionero sefardí by Alberto Hemsi published by the JMRC, no. 169, pp. 397-402). This version has become a popular song among Yiddish and klezmer musicians over the past few decades. Performers and adapters of it include Theodore Bikel who sings it in the folk-song medium, a Middle-Eastern inspired version by Frank London, and a hip-hop version by SoCalled (Josh Dolgin) on his 2005 album “The SoCalled Seder: A Hip-Hop Haggaddah.”

Additionally, a trend can be found in Yiddish songs to use the basic structure of “Ehad mi yodea” to compose secular songs with a similar poetic structure. This includes, first of all, a comedic song that was categorized by Ruth Rubin as a children’s song. This Yiddish song, with five stanzas, takes the recognizable structure of “Ehad mi yodea” and changes it into a whimsical song that connects between numbers and day-to-day objects. There is also a reference to the traditional line of God “who dwells and floats in heaven and on earth.” However, the content of the religious song is subverted, not necessarily in a positive way, as “one,” for example, represents the Jewish woman who does not dwell or float in heaven. Ruth Rubin writes about this song: “Among children, the number songs were particularly popular, and their counting of a particular number of things included the listing of animals, instruments, actions, objects, and the like, all of which may seem far removed from the original Passover chant. The following example [referring to the discussed version of “Ehad mi yodea”], however, does employ the Hebrew beginning of the Passover song, applying it humorously to secular objects, up to the number five.” (Rubin, 1963: 58)

Two different melodies to this song were documented. The first one was published in the collections of Moshe Beregovski [Example 4], Yehudah Leib Cahan and A.Z. Idelsohn. The first two are identical and there is only a minor difference between Idelsohn’s versions and theirs, with the first two in a 6\8 meter and Idelsohn’s in 3/4. The second melody differs both metrically and melodically from the first. It was published and arranged for piano and voice by Platon Brounoff in 1911 [Example 5].

One, who knows one? I know one:

One is a female Jew

Who doesn't dwell and doesn't float

Not in the heavens and not on the earth.

Two, who knows two? I know two:

Two ends on a stick,

One is a female Jew etc.

Three, who knows three? I know three:

Three corners of the dumpling,

Two ends of the stick etc.

Four, who knows four? I know four:

Four feet in a bed,

Three corners of the dumpling etc.

Five, who knows five? I know five:

Five fingers in a grasp,

Four feet in a bed etc.

Ehad Mi Yodea as a Wedding Song

The basic and recognizable structure of “Ehad mi yodea” was also used as a wedding song. Versions of this song appears in several collections of Yiddish folksongs including Ginzburg and Marek (1901) and Yehudah Leib Cahan (1957) Here the question and counting scheme are applied to topics associated with weddings and the bride and groom. Interestingly, in many versions of this song the numbers go up only to seven rather than thirteen. This can be a reflection, as pointed out by Chana and Yosl Mlotek, of the seven blessings that are part of the traditional Jewish wedding ceremony (Forverts 03.04.1977)

In the version of this wedding song published by Chaim Kotylansky in 1954 the song is referred to as “Echod Mi Yodea (Badchonish[1]).” Here the song goes up to four with one being God who makes matches in every place; two are the bride and groom; three are the klezmer musicians; four are the parents of the bride and groom (mehutonim). This version also has a recurring refrain and a translation of most of it is provided by Kotylansky: “Ram-tshiri-biri-biri-biri-biri-bim-bam I am a “marshalok” jester, and dance a “hoptshiktshok” in one shoe and one sock, in my hands a “yamshinshtok” and on my back a “labtzerdok.” (Kotylansky, 1954: 128)

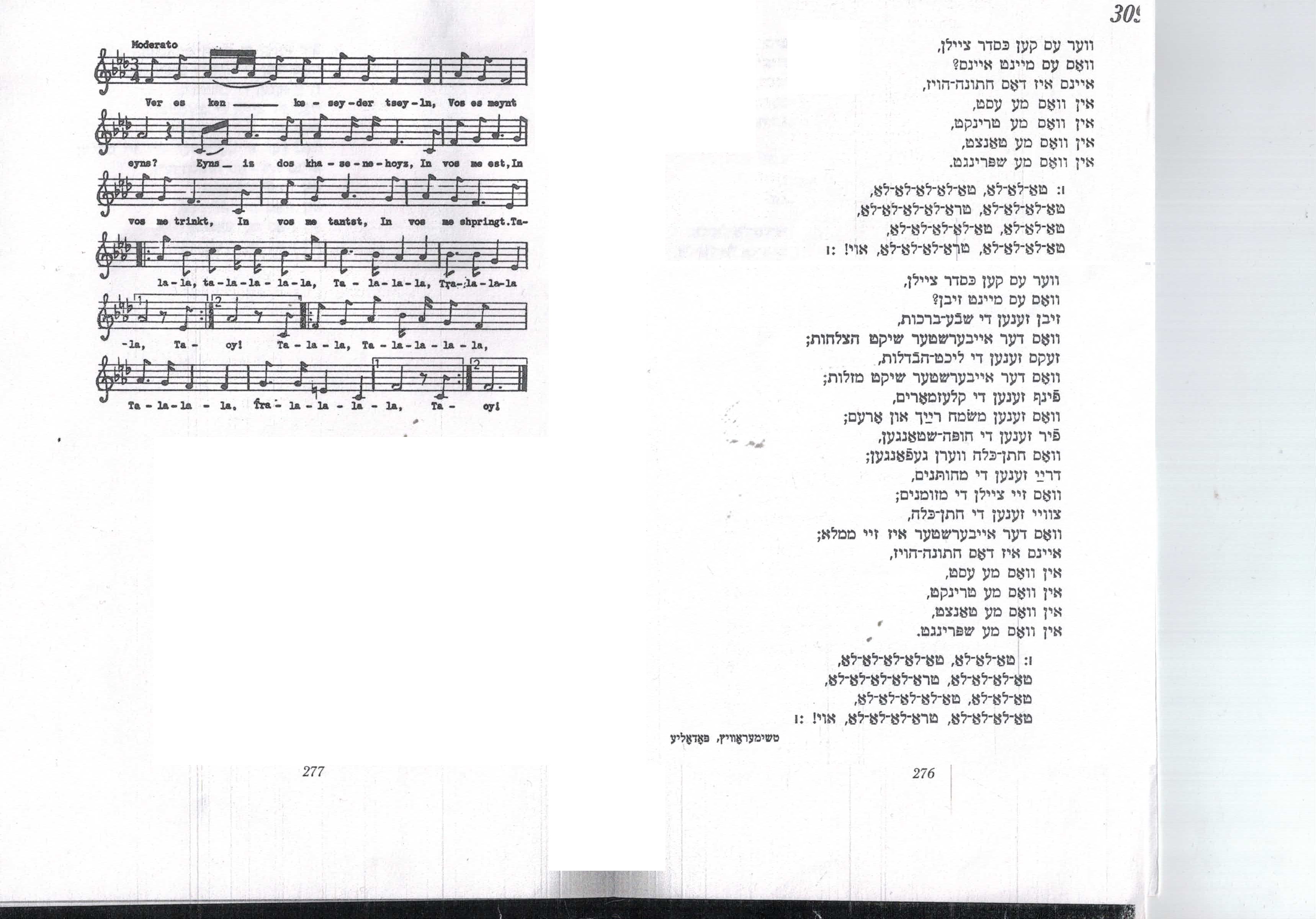

Cahan (1957) includes a version of the same song that begins somewhat differently [Example 6]. It was collected in Podolya and shares many similarities with the version by Ginzburg and Marek (1901). It opens as follows: “Who can correctly count, what is One? One is the wedding hall, where one eats, where one drinks, where one dances, and where one skips.” This stanza is followed by the refrain: “Ta-la-la, ta-la-la-la-la etc.” Some of the comparisons of the rest of the numbers overlap with the previous version, although some are found at different numbers: two are the bride and groom; three are the parents of the bride and the groom; four are the poles to hold up the khupe; five are the klezmer musicians, six are the havdoleh candles through which God sends luck; seven are the seven blessings through which God sends success.” (Cahan 1957:279-280)

Primary Sources

Cahan, Yehuda Leib. Yidishe folkslider mit melodyes. New York: YIVO, 1957.

Ginsburg, Shaul and Pesach Marek. Yidishe folkslider in Rusland. Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press 1991.

Kotylansky, Chaim. Folks Gezangen as Interpreted by Chaim Kotylansky. New York: YKUF, 1954.

Zalmanoff, Samuel. Sefer HaNigunim. Brooklyn: Ḥevrat Nihoah, 1985.

Studies

Bohlman, Philip and Otto Holzapfel. The Folk Songs of Ashkenaz. Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, 2001.

Fox, Chaim Leib. “Ehad mi yodea (Di Geshikhte fun a Lied).” Di Goldene Keyt 58 (1967), 224-228. (In Yiddish)

Fox, Menachem Tzvi. “On the history of the songs ‘Ehad mi yode’a’ and ‘Had Gadya’ in Israel and among the nations,” Assufot: Annual of Jewish Studies 2 (5748[1988]), 201-226. (In Hebrew)

Habermann, A.M. “Concerning ‘The Oriental Version of Ehad Mi Yode’a.’” Tarbiz 42 (1973), 210-211. Response to Sharvit 1972a (In Hebrew)

Rubin, Ruth. Voices of a People: The Story of Yiddish Folksong. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1963.

Sharvit, Shimon. “The Oriental Version of ‘Ehad Mi Yodea’.” Tarbiz 41 (1972a), 424-429. (In Hebrew)

Sharvit, Shimon. 'New Light on Ehad Mi Yodea.” Bar-Ilan Annual 9 (1972b), 475-482. (In Hebrew)

Sharvit, Shimon. “The Tradition of the Piyut ‘Ehad mi yodea’ in the Ladino Speaking Communities.” Studies in modern Hebrew and Jewish languages: Presented to Ora (Rodrigue) Schwarzwald. Edited by Malka Muchnik and Tsvi Sadan. Jerusalem: Carmel, 2012, pp. 599-611. (In Hebrew)

Tabory, Joseph. The JPS Commentary on the Haggadah. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2008.

Yoffie, Leah Rachel Clara. “Songs of the ‘Twelve Numbers’ and the Hebrew Chant of ‘Echod Mi Yodea’.”Journal of American Folklore 62, no. 246 (1949): 382-411.

[1] In reference to the badkhn the traditional Eastern-European Jewish jester who entertained the weddings.

Sound Examples

Images

Example 2

Notation to "ekh ti zimliak" taken from Sefer HaNigunim. Brooklyn: Ḥevrat Nihoah

Example 4

Children's parody of Ehad mi yodea from Beregovski's collection 1938 collection published in Kiev.

Example 5

Melody of children's parody of "Ehad mi yodea as it appeared in Platon Brounoff's 1911 collection Brounoff 1911.pdf

Example 6

Notation and 1st and 7th verses to the wedding song based on "Ehad mi yodea" found in I.L. Cahan's 1957 collection.