In this article we will review the development of the Nuba, which is considered the pinnacle of Andalusian music, from its origins in 9th century Spain, its arrival in North African countries in the fifteenth century, and through its coalescing into three main styles that continue through the present day –Morrocan, Algerian, and Tunisian. We will also discuss the scales and structure of the traditional Moroccan Nuba (Al-Ala).

Introduction

In the Maghreb, the Andalusian Nuba is considered the most important type of North African music. The music's origins can be traced back to 9th century Cordoba, Spain. It was created by the Arab musician Ali Ibn Nafi , known as Ziryab, who was active in the court of Harun al-Rashid in Bagdad until having to leave following a falling out with his teacher Ishaq al-Mawsili. He immigrated to Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain), and founded a new musical school in Cordoba, in the court of the Umayyads in Al Andalus (Muslim Spain). This school was based on the classical Arabic music of Bagdad mixed with other traditions that were prominent in Spain at that time, specifically the Christian-Visigoth tradition and the North African Berber traditions. This age-old synthesis formed the basis of the music that is known today as 'Andalusian.'

Ziryab's school became the most influential stream of Arabic music in Muslim Spain. Schools that taught the music that Ziryab created were founded in Seville, Toledo, Valencia, and Granada. Ziryab is also accredited with adding the fifth string to the Oud.

With the re-conquering of Spain by its Christian inhabitants, the Muslims were pushed to the south of Spain before being exiled from the country in the 15th century, maintaining control mainly in North African countries. This way the Arabic Andalusian music tradition arrived to the North African countries. However, it should be noted that during the preceding centuries, there was frequent contact and mutual influences between Al-Andalus and North Africa, and the Andalusian culture was known in and accepted in North Africa. Today there are three Andalusian Nuba traditions that are considered to be connected to older traditions that were transmitted orally by Muslim Spain's greatest musicians from the 9th century onward. They are: Tunisian- which originated in Seville; Algerian- which originated in Cordoba; Moroccan- the continuation of the Granada and Valencia schools. The Andalusian tradition can also be found in Libya (Ma'luf) with influences from the Tunisian Nuba. It should be noted that an important aspect of the preservation and development of the Andalusian music can be found in the Sufi Orders in the Maghreb who devoted a considerable part of their spiritual work to music and singing. In a similar manner, the Jews also adopted the Nuba as an essential musical component of their liturgy, specifically when singing the Baqqashot. There are some parts of the Andalusian tradition that were only preserved through the Jewish traditions. It is also important to note that alongside the music, there is an elaborate poetic corpus, which is a crucial element of the Nuba, since, as will be discussed below, the core of the Nuba is medleys of composed poems.

What is the Nuba?

The Nuba is a multi movement work (similar to the suite in western music), with a very complex system of connections between the movements. Similar to the Maqam that is found in Arabic music of the east, the Nuba is not only the notes of a scale but also the set of rules according to which the musical piece is composed. The researchers' assumption is that Ziryab created 24 Nubat that were based on 24 modes (or musical scales) that are called Tabai'a (Tab'a in the singular), one for each hour of the day. Today, in the Moroccan tradition (Al-Ala), 11 complete and five incomplete Nubat remain. The repertoire known in Morocco today is also referred as 'Al-Haik' or 'Haik' in short, after the poet Muhammad Al-Haik, who, in the 18th century, collected whatever repertoire remained in the memories of the poets and musicians of his time in order to save and preserve it. The other North African traditions have other Nubat: in Algeria (where there are 14 Nubat), in Tunisia (where there are 13 Nubat), and in Libya.

Scales and Intervals

The Andalusian scales are based on a system of intervals that differs from that of the Eastern Arabic music. Seemingly, the intervals are parallel to those of western music (tones and semi-tones), and if one would transcribe the scales and melodies in western notation, they would not need to use Eastern microtones (quarter and eighth tones as is customary in Eastern Arabic and Turkish music). However, it is important to note that microtones are used during performance, although without any clear rules rooted in classical theory. Additionally, because parts of Nubat that were not preserved in their complete form have been assimilated into some of the main Nubat, there are often modulations from the main scale during the performance.

The most common Nubat in the Jewish tradition are the Nubat of the Moroccan Tradition (Al-Ala) that are based on the following 11 modes (Tabai'a)

Raml al-Máya

Rasd al-Dayl

Iráq al-Ajam

Al-Máya

Rasd

Gharíbat al-Housayn

Hijaz Al Kabir

Hijaz

Al-Ushshaq

Al-Isbahán

Al-Istihlál [1]

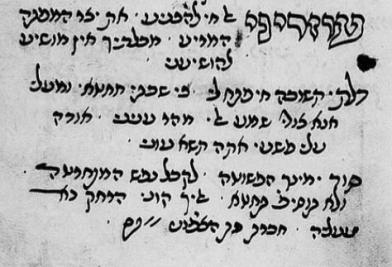

Picture: Tree of Modes, the classical classification of the modes of Andalusian music, excerpted from the manuscript al-Haiek from the library Daúd in Tetuán. Taken from the website La Música Andalusí

The Nuba – Structure and Performance

As previously mentioned, the Nuba's form is similar to that of a musical suite, that is to say, a musical work comprised of a number of movements. The Nuba is performed with an ensemble that includes an orchestra, soloist musicians, a choir, and soloist singers. The Nuba is comprised of two introductions and five movements. Each movement (Mizan) is characterized by a fixed rhythmic pattern from which it derives its name. Between the Mizans (movements), an improvisational section in free rhythm known as Beiten (two verses; see below) is performed. The five movements comprise the five main segments of each Nuba, and this structure is common to each of the three styles that were mentioned above.

The five central segments of the Nuba are:

|

Morocco |

Tunisia |

Algeria |

|

Basit |

Btaybhi |

Msaddar |

|

Qayim Wa-Nisf |

Barwal |

Btayhi |

|

Btayhi |

Darj |

Darj |

|

Darj |

Khafif |

Insiraf |

|

Quddam |

Khatm |

Khlas |

The Musical Structure of the Nuba in the Moroccan Tradition

1. Introduction 1: M'shaliya- The orchestra plays a few pieces in order to tune their instruments and to base the Tab'a (the musical scale) before the Nuba itself begins. The rhythmic character of this part is free. Sometimes soloist musicians play parts of this introduction in a free improvisation.

2. Introduction 2: Tuashia – the orchestra plays a few pieces that have a structured rhythmic character, which are played until the audience is seated and the right atmosphere for the performance of the five movements of the Nuba is created. Listen to Tuashia.

3. Five movements (that make up each and every Nuba) are performed: Basit, Qayim Wa-Nisf, Btayhi, Darj, Quddam. Each movement has its own rhythmic unit called Mizan (meter), which is why all the movements are referred to with the general name Mizan.

Basit

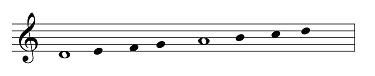

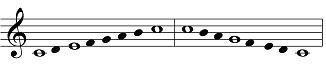

The Basit movement is based on a triple meter (three beats per measure) that can be performed by one of the following ways: three measures of 2/4, one measure of 6/4 or one measure of 3/2.

Qayim Wa-Nisf

This movement is based on a duple meter: two measures of 4/4 or one measure of 8/4.

Btayhi

The rhythmic structure of this movement consists of three measures that are sequenced in this way: 3/4+3/4+2/4 or 2/4+6/8+3/4.

Darj

This movement is based on duple meter, 2/4 or 4/4.

Al-Quddam

This movement is based on either 3/4 or 6/8 meters. In contrast with the Basit movement where the emphasis is on the second beat, in this movement the emphasis is on the first beat, and hence the rhythmic structure sounds different in the two movements even though they share the triple meter.

The Art of Performance

The Mizan

The performance of the Mizan begins with Tar playing (a type of frame drum) that is followed by a series of songs (Sana'a) that are performed without pause until the end of the Mizan. An important characteristic of the performance of the Nuba is the acceleration of the tempo in each Mizan, from slow at the beginning to a fast tempo at the end.

The different Sana'ai within each Mizan appear in a fixed order:

First song- Tasdira elula.

A number of songs in the Wazn meter.

First bridge – a song in which the tempo quickens.

A number of songs (up to four) in the faster tempo.

Second bridge – a song in a faster tempo than the previous songs.

A number of songs in the fast tempo (Insiraf).

A song that ends the Mizan – qfal

In between the different songs of the structural progression of the Mizan, folksongs called Barwals are performed. These songs are folksongs without a chorus that are used as a kind of recess. The have a strophic structure and the number of lines varies between the verses. The melodies of these songs are in the Andalusian folk style and are usually situated in the final Mizans of the Nuba (Darj or the Quddam), probably because of the relatively simple meters of these two movements.

The Basit

Because of the size of the repertoire and the extensive length of the complete Nuba progression, a full progression will never be performed in one night, that is to say a Tasdir (series) that includes all five Mizans and all their parts. In order to be able to skip parts, during the long and spread out parts of the Mizan -the Mouwassa` and Mazouz- songs called Basit are sung. The function of these songs is to act as a bridge within the Mizan and to allow the omission of certain parts through a progression that feels natural and organic within the entire structure.

The 'Beiten'

In between the different Mizans there is a transition segment called the Beiten (two verses). The text of this segment is comprised of two verses, usually taken from another song. The music is usually improvised on a melodic structure that is known beforehand, and it is used as a transition from one Mizan to the next, especially between the different rhythmic patterns of the two sequential Mizans.

There are two kinds of Beiten. The first opens with the mode's root note (the first note of the musical scale), and it is called 'mujtat'; the second type of Beiten opens with the fifth note of the musical scale (the dominant) and develops the musical progression around this note. The Beiten are characterized by being performed by soloists that perform musical progressions that ornament the melody's fixed structure. The Beiten's melodies are characterized by trills and melodic ascensions and declinations in a very free rhythm. Today there are twenty different Beitens, which are assigned to different Nubat, with each Nuba having its own fixed Beitens. Listen to Beiten.

The Sana'a

Each of the five movements of the Nuba (the Mizan) includes a sequence of poems-songs that are called Sana'ai (plural of Sana'a); these songs are performed sequentially and without pause in between them. The Sana'a is an Arabic poetic form whose origins are in the type of poem called the Moachah. This is the most important type of song in the Andalusian music and Nuba. The researchers are of the opinion that the Sana'ai that are performed today are not complete but rather are fragments that remain from a larger work. The Sana'a is usually comprised of five to seven lines. In each Sana'a there is one line that differs from the rest (the penultimate line), which is the most important. This line is called Taghtya (cover) and it usually comes with a musical change (rhythmic, melodic, modal). After the change, the music goes back to the main theme that began the Sana'a.

The Tasdir (seris)

To conclude this chapter on the performance of the Nuba, it can be said that a good performance begins with a correct building of the Tasdir (series of the piece). The conductor or leader of the ensemble confronts the vast repertoire of the Nuba from which he must choose and create his own Tasdir, that is to say, which songs will be performed in each movement. It is a personal decision, but one that is also influenced from a classical system of considerations. After building the Tasdir, the next focus is on the performance, since performing the Nuba is not like performing one song or a few songs that have no direct connection between them. It is up to the conductor to lead the orchestra during this long progression, slowly building up the energy from the slow and heavy to the fast and stirring, with each step having its own particular characteristic within the whole.

The Andalusian Music within the Jewish Piyyut tradition of North Africa

The Andalusian Nuba holds an important place not only in the art music of the Muslims of Morocco, but for the Jews of North Africa as well, especially within the Baqqashot ritual. Based on the large repertoire of the Andalusian Al-Ala, and in many cases they maintained the basic meter and tone of the Arabic original. This process reflects the deep connection of the Jews of North Africa to Andalusian music and culture; it allowed the Jews to adopt the Andalusian music into their liturgy and paraliturgy (Piyyutim).

Translated from the Hebrew original in 'An Invitation to Piyut' website, by Elie Adelman.

[1] According to Eilag-Ammzalag (1986) the Nuba Al-Istihlál is not an Andalusian Nuba but rather was formed in the 18th century by Alal Ibn Baltela and was used to replace the original Andalusian Nuba Istihlál Al-Dayl.