Preface

The history of the Jews, Heinrich Graetz, the great nineteenth-century German Jewish historian, once wrote, is essentially a history of suffering and saints, or Leidensgeschichte and Geistesgeschichte. Jewish Studies in this formulation consisted of the commemoration of a people’s collective suffering and the veneration of its rabbinic elites. In the twentieth century, scholars of the Jewish past have moved far beyond this constricting narrative to recover Jewish culture, economics, politics, and society. Yet something of that texts and tears, martyrs and saints approach still governs much of the practice of Jewish Studies and its approach to understanding the links between the lives and ideas of key individuals in the Jewish past.

A case in point is the scholar and musician Avraham Zvi Idelsohn, the founding father of modern Jewish musical research. Idelsohn’s life traversed several important arenas of modern Jewish history, including among other things the revival of Hebrew in Ottoman Palestine, the creation of a new secular Jewish culture, with a new national repertoire of Zionist songs, the internationalization of Jewish scholarship, and the creation of modern Jewish music as a whole. He left behind a legacy of iconic books and cultural artifacts that still define in many ways the Jewish musical imagination in both its scholarly and popular forms. But Idelsohn the man himself remains an enigmatic, elusive figure. In a way, he, too, is like the medieval rabbis so beloved by Jewish Studies—a disembodied male mind, torn from the contexts of his family and social context, sanctified as a secular saint of Jewish sound, whose life was characterized by endless wandering and ended in personal suffering.

What is missing from our understanding of Idelsohn is his connection to the European Jewish fin-de-siecle as he experienced it across the Baltic region, urban Germany, Ottoman and early British Palestine, Lithuanian Jewish South Africa, and Midwestern American Reform Judaism. What is missing is a picture of the husband and father, friend and rival, teacher and entrepreneur, artist and academician—and how these roles overlapped and defined themselves against one another in his decades of activity.

In short, we know little of the man behind the myth.

As part of our ongoing collaborative research project, Edwin Seroussi and myself have been engaged in a multi-year survey of existing and new archival sources related to the life and work of Idelsohn towards the completion of his biography. It was in the context of this work that in the fall of 2016, Seroussi located a major cache of Idelsohniana in the Idelsohn Archive at the Music Department of the National Library of Israel (catalogued as Mus. 4). Among the many treasures in this collection, Seroussi identified a previously unknown handwritten memoir by Shoshanah Idelsohn, the musicologists’ eldest child. This document, written on a few pages detached from a pink paper pad, offers the reader a unique window into the inner daily life of Shoshanah’s father, a rich portrait of a complex personality whose complete dedication to his life project was at times detrimental to his duties as head of a young family.

We are pleased to publish this text here in translation for the first time as part of our larger endeavor to untangle Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, the man and his work in their historical, social and intellectual contexts.

James Loeffler

A.Z. and Zilla Idelsohn in Cincinnati, exact date uncertain.

Introduction

The life and works of the musicologist Abraham Zvi Idelsohn (1882-1938), a key figure in the modern constitution of Jewish music as a bona fide academic field of inquiry continues to attract wide attention. Yet important details regarding his remarkable and stormy life are still lacking or not fully addressed and certainly not well understood. Idelsohn’s earlier years in Europe and South Africa prior to his pivotal immigration to Ottoman Palestine in 1907 are covered scantly, if they are mentioned at all. Jehoash Hirschberg, the only researcher thus far to have mined the rich Idelsohn archive at the National Library of Israel, covered certain aspects of Idelsohn’s Jerusalem period (1907-1921, with some interruptions) with emphasis on his interventions in the institutionalization of the music life in the Jewish community of late Ottoman Palestine (Hirschberg 1995, ch. 1). Finally, Judah Cohen (2010) has addressed Idelsohn’s American period (1922-1935) in more detail than any previous treatment of the subject by other scholars.

Idelsohn himself left a rather short autobiography in English and Hebrew published towards the end of his life, when his health had already seriously deteriorated (see Schleifer 1986a). His tone in these texts was rather laconic and somber. As any autobiography, the writer presents a selection of facts that he wanted to endow to posterity. As Schleifer shows, he also shifted the emphases in both versions, having in mind the diverse Hebrew and English readerships. Almost totally absent from this text are the members of his family who, as we shall see, played a distinctive role not only in his personal life as expected but also in his scholarly endeavors.

We hope to start filling the gaps in our knowledge of Idelsohn’s persona by publishing the following touching and yet extremely informative document located in the Idelsohn Archive at the National Library of Israel and catalogued as Mus. 4, G8. It is a memoire by Shoshanah, Idelsohn’s eldest child. It was written in South Africa, where most of Idelsohn’s heirs eventually settled and is undated, but was obviously written after Idelsohn’s death in South Africa in 1938. The document is part of a rather new section of the Idelsohn archive and therefore Adler and Cohen (1974) did not include it in their initial catalogue of this archive. Hirschberg (1995: 21, n. 129) briefly mentions this document.

For the sake of contextualization, we have annotated the text in a rather extensive manner and corrected some mistakes that derive from the author’s distance from the events described in it. This text must be read in the future in conjunction with the memories of Shoshanah’s sister, Yiska, Idelsohn’s fourth and youngest child. Yiska recorded her memoires by herself on tape over twelve days (360 minutes of testimony) on her son’s farm in Tzaneen, South Africa when she turned 84 in 1995. Jonathan Misha Morgan, the grandson of Denah Idelsohn, Shoshanah’s second sister and great-grandson of A. Z. Idelsohn, transcribed and published substantial sections of this precious oral testimony online in 2009. This material is available in the website http://www.seligman.org.il.

Shoshanah Idelsohn was born in Leipzig, Germany in 1905 and moved to Palestine with her father, mother and younger brother Eliyahu in 1907. She left Palestine for Berlin with her father in 1921 and studied at Heidelberg. According to Yiska’s testimony, Shoshanah became sick in Germany and “In 1923 father’s younger sister Becky, her husband and her two young sons from Johannesburg visited Riga in Latvia and they stopped in Berlin. She suggested that Shoshana whose health had not fully recovered accompany them back to Johannesburg where the climate would be more agreeable. Ima [Yiska systematically refers to her mother, Zilla Shneider, in Hebrew as does Shoshanah] had to make a quick decision. It was very difficult to part with our dear sister but in her own interest it was decided she should accompany Becky back to Johannesburg.”

While in Berlin, Idelsohn started to tour Europe and later on the USA (where he arrived on November 15, 1922), settling eventually in Cincinnati for the academic year 1924/5. When he moved to Cincinnati, his family returned from Germany to Palestine. Zilla, Dinah and Yiska lived for a brief period in Tel Aviv in 1924/5. Idelsohn returned to British Palestine to rejoin his family and left Eretz Israel for good on October 5, 1925, embarking with his wife and two younger daughters, Dinah and Yiska, aboard the SS “Braga.” They arrived to Providence, Rhode Island on November 4, 1925 on their way to settle in Cincinnati. Therefore, there is a discrepancy: according to Yiska’s testimony, Shoshanah was separated from her parents for ten years (1923-1933) while according to Shoshanah herself, she left for South Africa already in 1921 and did not see her parents for twelve years. In 1927, Zila and Dinah returned to South Africa, while Yiska remained with his father in Cincinnati (from Yiska’s own oral memory).

Thus, the starting point of Shoshanah’s text and in fact its inspiration is her 1933 journey to the USA to bring her ailing father and mother (who had returned to Cincinnati apparently after 1931 to assist his husband after his health failed) to join the family in South Africa. During the long trip, she tried to imagine her parent’s faces “and all sorts of memories from my youth flashed through my mind.”

The importance of Shoshanah’s account relies on her genuine description of intimate scenes from the daily life of the Idelsohn household in Jerusalem. It is written in a flawless modern Hebrew, betraying her upbringing and schooling in the new Hebrew-centric Jewish society of late Ottoman and early British-ruled Jerusalem. The intimacy of her narrative, and most especially her loving memories of her parents, sharply contrasts with the detached and rather monotonous tone of Idelsohn’s own autobiography. In addition to her descriptions of family scenes, such as journeys to nature or home celebrations, she provides precise information relating to events and individuals in the life of her beloved father. Among the events one must single out the anecdote about the sparking moment of inspiration of the opera Yiftah and the participation of Idelsohn’s choir in the Hebrew University cornerstone placing ceremony held on July 24 of 1918.

The memoire transmits the persistent instability of the Idelsohn household in terms of financial security and dwelling locations. Frequent moves between Jerusalem’s emerging Jewish western neighborhoods outside the Old City are noticeable. Idelsohn’s total, even obsessive, dedication to his research at the expense of daily matters also transpires from this text (her sister’s Yiska’s later oral memoire stresses this issue with certain bitterness). Particularly moving is Shoshanah’s description of the total devotion of her mother to his father’s mission, not only as a housewife but also as a research assistant.

Yiska’s following description of her sister Shoshanah, adds an additional dimension to Shoshanah’s personality and relationship with her father: “Shoshana’s love for dancing the horah and Russian kozatskas [read: kozachoks] always remained with her and she never did abandon her singing. Father groomed her to be a lovely soloist in his choir in Jerusalem. She alone went with him to Berlin where she assisted A[braham] Z[evi] transcribing his lyrics and in his work. She had a beautiful Hebrew handwriting.” The document presented hereby thoroughly validates this last statement.

Edwin Seroussi

The Text

In the year 1933 I sailed from South Africa to America to visit my parents who were living in Cincinnati, Ohio and whom I longed to see. Nearly twelve years had passed since I had last seen my father and bid him farewell. At the time [1921] I was only sixteen years old, and [now] I was married and the mother of two daughters. While journeying by ship, I tried to imagine their faces and all sorts of memories from my youth flashed through my mind.

The first memories that arose in my head were from the time we lived in Zikhron Moshe,[1] in a one-story house with one long side and two short wings, shaped somewhat like the Hebrew letter ‘nun’ which was surrounded by a little garden where my brother Eliyahu and I played.[2] I was then [1908] three years old. Mother [Zilla Schneider 1882-1958; married Idelsohn on October 2, 1902 in Leipzig], a gentle woman, had a long, pale face. Her hair was black and just a little curly and her eyes, a dark brown almost black, were full of expression and warmth. Her nose was a bit elongated, but still pretty and her mouth, of medium size with soft, rosy lips. Her face radiated light, affection and indeed Mother was a good woman, devoted to her husband and children. Her kindly spirit was always apparent when she spoke in her sweet and pleasant voice. She was not a tall woman, only about five feet and two inches and she had a plump figure but was not fat.

Father was taller than Mother, approximately six feet tall, robustly built giving an impression of a strong and energetic person. He had a large head, set low on a short neck. His eyes were large and brown and he wore spectacles. His nose was straight and slightly long. His comely mouth was covered by a mustache and graced by a small beard. His teeth were straight and lovely as pearls and his lips could be seen only when he laughed. His face always looked a bit tan because he loved the fresh air and sunshine. He was pedantic about order and tidiness. He was always neat and meticulous not only in his attire, but also in his room that was always tidy and ordered. No one was allowed to move or touch anything in his study.

Father had a musical baritone voice. His study, at the back of the house, was frequented by many guests. Visitors of many backgrounds came to see him, Hasidim, Yemenites, Arabs, fallahim,[3] Georgians, Sephardic Jews, kushim,[4] Galician Jews and so forth. All sorts of sounds emanated from his study. On many occasions, my brother and I would peek through the window to get a view of what was going on in his room. We could see different types of people and their varied manners of expressing their feelings and opinions. The Galicians made us laugh the most because they loved to show their emotions through song, dance and gesturing with their hands. Father stood by his desk on its tall legs and rapidly transcribed [the songs], while they sang, [into] musical notations.

Frequently the visitors arrived at lunchtime, sat down next to us, and belted out as loudly as they could many different melodies. I stared at Father’s face as he sat captivated by the melodies, leaving the meal set before him untouched. Mother would look at him silently with concern. The only time we could live our life without the intrusion of strangers and visitors was on the Sabbath eve and Sabbath days and holidays, then Father would be delighted and happy and the entire house would be filled with song and joy. Every time after a meal, he would teach us new zemirot – Sabbath songs – and all of us would be entranced by our own joy.

As we grew up, every Sabbath [before] dawn we would leave the house, go hiking in the mountains, and wait for the sunrise. The sky would fill with beautiful colors and hues enchanting us with the glory of their loveliness. While we were in Jerusalem, it was our custom to take these hikes.

The birth of my sister Dinah in that very same house in Jerusalem was the occasion for great celebration.[5] Hundreds of people came to congratulate my parents and to share our rejoicing. We lived in that house only a very short time and even the name of the street I have forgotten. From there we moved [in 1909 or early 1910] to Ethiopia Street [Rehov Hahabashim in Hebrew; Abyssinian Street during the British Mandate] where our home was close to Eliezer and Hemda Ben-Yehuda’s house.[6] My parents immediately became friends with the Ben Yehuda family. I was surprised to hear them speaking in the Hebrew language and what amazed me even more was hearing the servant girl replying to them in Hebrew. They were the ones who influenced us to speak in Hebrew and only in Hebrew in our home.

During our stay at the [house in the] Ethiopia Street, Father opened a cantorial school in our house and many young men came to study with him. Among them were some who sang in exceptionally lovely voices. At this time I began to attend kindergarten. Frequently, Father would ask me to sing for him. His students would stand around me and listen to the songs I sang. It was quite apparent from the expression on Father’s face that he was dissatisfied with the songs I sang. Once I saw him in the kindergarten speaking to the kindergarten teachers who gathered all of the children together and all of us sang the same songs that I had sung previously for him. Again I saw the same disappointment on his face. However, years would pass before I realized that the reason for his disappointment was [because] the Hebrew songs were sung to foreign folk melodies. I am certain that the kindergarten songs of that time were what gave my Father the impetus to compose original Hebrew melodies for children’s songs.

His work life was strenuous. During the day he taught and at night he was busy investigating the science of music (torat haneginnah) and writing down his new findings [Heb. hidushav, lit. “innovations”]. Mother would tell me that Father frequently worked until dawn, resting only briefly before his students arrived at our house.

While I was a pupil at the Lämel School, the upper classes arranged a students’ gala performance to which all of the pupils of the school and their parents were invited. Father and I also went. The staged performance [Heb. hizayion] included a dance of Bat Yiftah who, with her friends, went out to greet the victorious Yiftah. As we returned home, the entire way, my father was absorbed in his thoughts and hummed a tune to himself. It was hard for me to contain my excitement about the play.[7] I very much wanted to speak with him about the performance, but did not dare interrupt Father in his thoughts. When we arrived home I had no opportunity to talk to anyone about the gala performance. The house was shrouded in darkness and Mother was asleep.

The next morning, I ran to Mother to tell her about the dance I had seen. She told me that Father had worked all night long in his study as that she heard him humming and talking to himself, murmuring the words Yiftah and Yiska many times out loud. After telling her about the dance I had seen, Mother said that the gala performance at the Lämel School inspired Father to compose the opera, “Yiftah.”[8] His study was full of papers in his handwriting and Mother simply did not know how to maintain a semblance of order in it. Finally, she managed to get a large box that stood in a corner of the study and there she would collect all of Father’s manuscripts.

At that time, my grandfather, my father’s father came to visit us from Courland which was a truly happy occasion. [9] Grandfather was a man of medium stature, with a long beard and black, fiery eyes full of affection when he gazed at us, his grandchildren. He loved taking a walk with us and bought various sweets for us along the way. While he was staying with us, my younger sister was born and Father called her Yiska, the name he had given to the daughter of Yiftah in his opera.[10] When she was six months old, my father decided to go away for a respite. All of us, together with Grandfather, travelled by wagon to Jericho. However, the weight of us was too much for the horse to pull, so Father and we, the older children, got off the wagon and walked on foot behind it. We walked over hills and fields, empty of houses and tents. We did not meet a single person along the way. The air was fresh and lovely and we were full of gladness, all the while singing all sorts of songs. I looked at Father's face and was amazed by how youthful he appeared, like a young fellow.

When we reached Jericho, we stayed at a hotel owned by Arabs. Everything there was in a very primitive state. Date palms grew around the hotel providing shade beneath them. We saw the Dead Sea from afar and we walked there to bathe. Father and our grandfather had long conversations by the sea, but I could not abide the salty water that stung my eyes so much that I had to get out of the sea to sit on the beach with my mother and little sister. We remained in Jericho several days, returning home the same way we had come.

Upon our return home, our grandfather went back to Courland to his family and we all felt his absence.

Meanwhile an orphanage for girls opened opposite our home.[11] We visited the orphanage quite frequently especially after the Sabbath ended. Every time we visited, they happily welcomed Father, imploring him to teach them new songs.

We moved again [1912?] from the Ethiopian’s Street back to Zikhron Moshe to a nicer house than the first one. There, Father began to teach in the Seminar and Kindergarten Teachers’ School. He also taught in the upper classes of the schools.

Many celebrations were held in Eretz Yisrael and Father was invited with his choir to most of them to sing for the audience songs he had composed and folk songs. I enjoyed seeing Father conduct and listening to his choir sing with such fervor. I was sorry that Mother could not participate in this enjoyable pastime, because she had to stay home and care for my sister, the baby.

One day upon returning from school, Mother told me that Father had gone abroad [1913] to publish his manuscripts. Since he did not want to make us sad, he did not want to tell us about this before leaving [on his trip].

While he was abroad, a quarrel broke out between the teachers of the Hilfsverein School and the teachers at the Hebrew School that had just been established. The teachers at the Hilfsverein opposed the establishment of a Hebrew School.[12] The disagreement did not disrupt the establishment of this school and most of the pupils who studied there continued to attend there. Among them we too studied there according to the advice that Father had written to Mother. [13] When he returned home, there was great happiness in our household. Father’s face beamed with joy at seeing us and his friends who came to see him. He recounted his success in Vienna especially how he had persuaded some important persons to take an interest in the history of music that he took with him. One of them was Professor Karabacznick (read: Karabacek).[14] He also told us about his meeting with Bialik at the [Eleventh] Zionist Congress [September 2-9, 1913] who had asked him to consider writing articles in Hebrew for his journal, Reshumot. In addition, he met Dr. [Moritz] Güdemann, head of the Jewish movement and many famous rabbis.[15]

Quite suddenly, the First World War broke out. At this time [1914], we were living in the Ezrat Yisrael neighborhood.[16] Father was drafted by the Turkish Army and appointed director of the army’s band.[17] Life in Eretz [Israel] was extremely hard. All sorts of diseases broke out and spread among the inhabitants of the country due to lack of food and poverty. All of the women managed their households and watched over for their children like women of valor. It was miraculous in my eyes even today, how Mother managed to prepare wonderful and tasty meals with the few pennies in her possession. Finally, with the English conquest the country, the war ended and Father returned home.[18] At this time, Mother appeared exhausted and Father arranged for her to travel to Motza, which is near Jerusalem, for a holiday.

During the war, all of the wagons and horses disappeared from Jerusalem, and the only way one could one travel from place to place was by riding a donkey. Father hired a donkey and a young Arab to lead it so my mother and younger sister could ride on its back. Of course, not all of us could ride together on the donkey, so we decided that Mother would ride ahead with the babies to Motza and the Arab would return the next day to fetch the rest of the children. When the Arab appeared at our house, Father was afraid to leave us alone in his hands and so he asked a Yemenite who worked at the school to accompany us. All the way to Motza we spent laughing at how the Yemenite poked fun at the Arab. Frequently he tried to hide from the Arab in the mountains we passed through. The poor man became alarmed every time he did not see us because he suspected we had stolen his donkey. The narrow path from Jerusalem to Motza twisted and turned among the boulders of the mountains and wild shrubs that grew there. Everything was dry, without a single living soul. In passing, there was only one Arab village, Lifta, comprised of small earthen dwellings surrounded by scrawny Arabs, dressed in filthy garments, their eyes just barely visible because they were covered in flies.

Finally we reached Motza. How the scenery had changed! A variety of trees grew all around, several houses were scattered among the mountains and in the distance we could hear a waterfall.

Mother was already lodged in a house surrounded by pretty flowers and plants, located next to a spring whose waters flowed in channels to irrigate them.[19] We were delighted to see the spring's pool and immediately we disrobed, jumped in and bathed our bodies from the sweat and dust of our journey. The water was fairly cold and very pure. After the bathing and dressing, we felt hungry. Of course we had to bring the provisions for our meals with us. The Yemenite woman, wife of our companion in the journey, prepared delicious foods for us in the Oriental manner. We consumed the meal with a hearty appetite in the shade of trees, listening to sounds of the waterfall and were overcome by complete tranquility. When Mother had regained her strength, we returned home.

In 1917 the Balfour Declaration was granted which influenced Jews in the Diaspora to immigrate to Eretz Israel. Also a Jewish High Commissioner, Herbert Samuel, was appointed in Jerusalem.

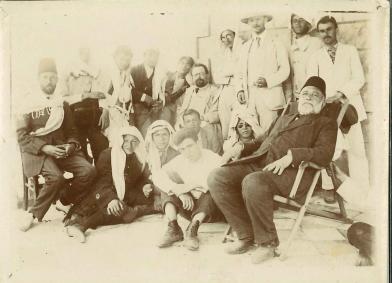

At this time plans started to lay the cornerstone [Heb. original: yesod, the basis] for the Hebrew University on Mt. Scopus. A ceremony [Heb. original, neshef, a party] was organized one day for the laying of the cornerstone. Father and his choir, of course, performed his Hebrew songs in the ceremony that was held in the presence of hundreds of people who had come to watch.[20]

The economic situation began to improve in Eretz Israel because a stream of [immigrants] from abroad started to arrive to the country and found [new] towns, kvutzot and moshavot. Our economic situation at home also improved.[21] Father devoted more time to his work and Mother assisted him in composing melodies. Since we children were now older, we helped her with the housekeeping, allowing her to devote her time to Father.

Frequently in the evenings, I saw both of them engaged in composing different melodies. Mother was blessed with a special talent for composition. When she listened to Father reading some lyrics, Mother could sing a tune for him. Many of the melodies he composed were due to the influence of songs she sang and she contributed quite a bit of material for the melodies of his music. (I have many melodies that Mother composed after Father's death.)

The growing number of Jewish immigrants necessitated the opening of additional schools in Jerusalem. There were very few teachers and they worked extremely hard because they taught at the three schools that already existed at the time. Despite his jobs teaching at the above mentioned schools, at the Men’s Seminar and the Kindergarten Teachers School,[22] he decided to establish a music school. Finally, following many difficulties, he was able, with the assistance of the [British] Mandate Government, to open the first music school in Jerusalem. Among the British soldiers discharged from the British army, he found two, Mr. Seal, who played the piano and Mr. Katshowski, who played the violin who devoted themselves to teaching music at his school.[23] Father taught music theory and singing. A year later, Father was very pleased to learn of his students' success in their exams and progress in playing the piano and violin that encouraged him to continue with his work. At this time in Jerusalem, only a very few wealthy persons owned pianos, and other musical instruments were hard to come by. The students could practice at the music school on the piano and violin only when the teachers did not need them for lessons.

When I was about 13 years old [1918], Father wanted all of us to settle on a moshav because he considered it healthier to live there. So he purchased a small plot of land in Har Tuv and had the Bekhar family to oversee it. Mother tried to cut her expenses to cover for the development of the land and buy all sorts of plants, like olive trees and grape vines, and similar [plants]. To my great disappointment, we never had the opportunity to live there.[24]

Once while Father was in Har Tuv, he observed a white Arabian horse and devoted [to it] an article in the newspaper, Ha-Doar (The Mail), describing his beauty, movements and speed along with his wildness that made him untamable by a human being. Impressed by his story about the horse, I wanted to go and see it myself. With my parent’s permission I went there and after settling in a room at the Bekhar family’s home I set out to look for the horse and found him standing by a mound of wheat munching the sheaves with appetite. Quietly I climbed up on the pile of wheat, leapt on the horse’s bare back, and immediately grabbed his neck. When the horse felt my weight on his back he began to jump around and gallop, trying to fling me off. The more he jumped about, the harder I held onto him with my hands. He began galloping on the hills from rock to rock and in the end succeeded in tossing me off where fortunately, I fell into a grapevine! Of course I was scratched and scraped by the branches of the grapevine and my clothing quite torn to shreds. That was the last time I saw my parent's plot of land in Har Tuv.

Around the year 1920, the first of the riots began in Jerusalem. The inhabitants of Eretz Israel were shocked, but the younger generation inspired by [Vladimir] Jabotinsky set out to fight against the Arabs. The Arabs were taken by surprise and frightened, scattered to every corner of the city. I saw this with my very own eyes as I peered through the window of our home that overlooked the field next to Nablus Gate.[25]

At this time, Father was invited to Europe in a matter pertaining his work. We all left Eretz Israel. The journey from Jerusalem to Jaffa took a very long time, exhausting all of us. We travelled the entire night in a wagon. The Arab owner of the wagon was forced to change the iron horseshoes a few times and to let the horses rest a bit.

When we reached Jaffa, we were happy to get off the wagon and stretch our legs. We embarked on a small French ship that sailed for Marseilles. Mother and I had an unpleasant voyage as we both suffered from seasickness while Father and my brother and sisters enjoyed the sailing.

From Marseilles we travelled to Germany, and upon our arrival, Father immediately set out to find publishers who would print his books and finally decided to journey to Berlin. In 1921, we lived with Father in a private boarding house near Magdeburg Palace. There, Father found a publisher who would print his books. Both of us were busy day and night copying his manuscripts.

Father formed a choir of cantors to sing Hebrew songs for records. One day [in 1922] Father took me to Polydor Deutsche Gramophone to see and hear how the choir sang. It was not so easy to teach the cantors to sing together in harmony and in such a way that their voices would make a ‘clean’ recording on the records.[26] The names of the cantors who sang were: [Salomo] Pinkasowicz,[27] Yossef Bernstein [sic, read Iosef Bornstein] and others whose name I cannot remember.[28] Mr. Diamond [sic, read Jacob Dymont] accompanied them on the piano.[29]

When Father was immersed in his work, a deep furrow would appear between his eyes, his emotions were reflected in his eyes and his lips twitched in different ways. While he conducted a choir, his hands gestured in a lovely manner, following the rhythm of the music and the movements of his entire body conveyed his feelings. When Father completed his contracts with the various publishers, he left Berlin and began to travel from city to city to lecture about his work. He delivered lectures in Berlin, Amsterdam, Paris, Vienna and London. In the end, he traveled to New York. In America, he met his good friends, Professor Samuel [S. Cohn] and Mrs. [A. Irma] Cohn who had helped him throughout his lifetime in his work.[30] They were able to arrange a position for him as a professor of Jewish music [Heb. neginnah ‘ivrit] at the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, Ohio.[31] Mother and my sisters travelled there and made a home with Father. A large portion of his books and articles on Jewish music and liturgy, prayers and cantorial music that had not been published in Germany were published in America.

Father taught at the college for a number of years until about 1930 when he suffered a brain hemorrhage.[32] In the first years of his illness, he still managed to teach at the college, despite having difficulties in the pronunciation of some words and having some trouble walking. Slowly but surely his illness worsened until he lost his voice completely and his right side became paralyzed. Now he could no longer write and was nearly unable to walk compelling him to resign his position. When I arrived in America [in 1933] and met my parents, I could not believe that this was Father, the same man I had parted from in my youth. His face and body were gaunt, his eyes which formerly had been so full of life, were now filled with sadness and pleading. I could not discuss [Heb. lehitvakeah, lit. to argue] with him because his tongue was completely paralyzed. Most of the time, he sat absorbed in his memories. Once while I was holding a book as I read an article to him, he showed me letters with his finger and I understood that he [still] had so much material in his mind. To my great sorrow, we never found any way or means to understand him that would enable us to write down his ideas for him.

Mother also had changed a lot, having aged and grown very thin from her concerns for Father and the burden of caring for him during his illness. However, she never complained about having to dress and feed him like a baby.

Translated from the Hebrew by Tali Schach.

Edited, commented and annotated by Edwin Seroussi.

References

Adler, Israel and Judith Cohen. 1976. A.Z. Idelsohn Archives at the Jewish National and University Library: Catalogue. Jerusalem. (Yuval Monograph Series IV).

Cohen, Judah M. 2010. Rewriting the Grand Narrative of Jewish Music: Abraham Z. Idelsohn in the United States, Jewish Quarterly Review 100, no. 3, pp. 417-453.

Hirshberg, Jehoash. 1995. Music in the Jewish Community of Palestine 1880-1948. A Social History. Oxford University Press.

Idelsohn, Abraham Z. 1986. My Life: A Sketch, Yuval 5: The Abraham Zvi Idelsohn Memorial Volume, pp. 24-28.

Nemtsov, Jascha. 2014. Ein jüdischer Synagogenmusiker im Berlin der 1930er Jahre: Jakob Dymont und seine Freitagabendliturgie, Pardes 20, pp. 47-60.

Schleifer, Eliyahu. 1986. Idelsohn’s Scholarly and Literary Publications: An Annotated Bibliography, Yuval 5: The Abraham Zvi Idelsohn Memorial Volume, pp. 53-180.

Endnotes

[1] A neighborhood in central Jerusalem founded in 1905, bordered by Geula to the north, Mekor Baruch to the west, David Yellin Street to the south, and Mea Shearim to the east. It was one of several neighborhoods in Jerusalem named in honor of Sir Moses Montefiore. Its first inhabitants were teachers associated, as Idelsohn was, to the Lämel School, one of Jerusalem's first modern Jewish schools. Built in 1856 with funds donated by Elise Herz Lämel of Vienna, German-Jewish philanthropic societies managed the school until 1910, when the Hilfsverein der Deutschen Juden, a German-Jewish relief association established in 1901, took over. The Hilfsverein employed Idelsohn until the break of World War I.

[2] Eliyahu Idelsohn was born in South Africa in 1907 just prior to the Idelsohn family move to Palestine. He died in Brazil in 1959/60 and not in his early infancy as published (cf. Introduction to Idelsohn 1986).

[3] Fallahim are Arab peasant farmers.

[4] The word in Hebrew, Kush appears a number of times in the Bible with a geographical reference to a location south of Egypt or around the horn of Africa. In this context it refers to Ethiopians.

[5] Dinah/Dena Idelsohn was born on April 19, 1909 and died in Johannesburg, on November 16, 1981. She left Palestine with her parents and her sister Yiska in 1925 (see our introduction) and immigrated to South Africa on November 21, 1927, after spending two years with her parents in Cincinnati.

[6] Ben Yehuda lived from 1909 to 1922 (the year of his death) on 11 Ethiopia Street just in front of the Ethiopian Church located on 10 Ethiopia Street.

[7] It is impossible to determine exactly which play Shoshanah and her father attended as there were by that time several Hebrew and Yiddish plays on the subject. One sound possibility is the rather rare unpublished Hebrew play of that name by Shlomo Feinstein (1872-1961) who wrote it in the Jewish settlement of Sejera (Heb. Ilaniya / Ar. al-Shajara) in the Upper Galilee for performance at the Hebrew school he established there. See, Eliyahu Hacohen, http://onegshabbat.blogspot.co.il/2017/01/blog-post_20.html

[8] On the opera Yiftah see, Hoffman in Idelsohn 1982: 42-43 (Hebrew section); Yehudit Cohen, Yiftah: Hizayion negini me-et A. Tz. Idelsohn, Taslil 15 (1975): 127-131.

[9] Ger. Kurland, a district in Western Latvia on the shore of the Baltic Sea. Idelsohn’s family originate from the village of Feliksberg (or Felixberg; Jūrkalne in Latvian), located in this district.

[10] Yiska Idelsohn-Klempner-Schmaman was born in 1911. She moved from Palestine to the USA with her mother and sister Dinah to join her father in 1925. On October 10, 1931 she married Solomon Klempner (a family from Tel Aviv) in Johannesburg (The Zionist Record, October 16, 1931). Her second marriage was to Herman Schmaman. She passed away in 2007. She and her second husband were pivot figures in ensuring the transfer of the Idelsohn archive to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

[11] Known as Hama’on li’vnot Israel (The Home for the Daughters of Israel) the institution was established in 1907 by Efraim Cohen Reiss and was supported by the Germany-based Ezra (Hilfsverein) organization. It was located on Ethiopia Street no. 8 and considered a “modern” and selective institution where Hebrew was the spoken language in opposition to the orphanage of the Ashkenazi community run by the Haredi community where Yiddish was spoken. See, Efraim Cohen Reiss, Mizikhronot Ish Yerushalayim, Tel Aviv: Shoshani, 1934, vol. 1, pp. 246-8.

[12] The reference here is to the famous episode known as the “War of the Languages” whereas a group of eighteen teachers resigned in 1913 from the Ezra seminar (the Hebrew name of the Hilfsverein school) under the leadership of David Yellin (1864-1941), the deputy director of Ezra, and constituted the new Hebrew College for Teachers (Beit ha-midrash le-morim ha-‘ivri). The aim was to create a national, Hebrew-based institution for teachers’ training that would be independent from any foreign intervention. Yellin had close contacts with Idelsohn.

[13] It remains unclear whether Shoshanah means that the students, including herself, continued to attend only the new Hebrew School or the Hilfsverein School while also attending the new Hebrew School.

[14] The reference is to the Orientalist and Chief Librarian of the Imperial Library Joseph Maria (Ritter von) Karabacek (1845-1918). See: Hans L. Gottschalk, Karabacek, Joseph von, Neue Deutsche Biographie, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1977, vol. 11, p. 140, available online: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/0001/bsb00016328/images/index.html?seite=154. This name is also disfigured in Idelsohn’s autobiography (Schleifer 1986a, p. 21). Idelsohn describes him as “the well-known anti-Semite.” In spite of this remark, Idelsohn adds that the influential Karabacek was cordial to him and facilitated the grant from the Imperial Academy of Sciences for continuing his research in Palestine. Karabacek’s wife Karoline Johanna Lang was, by the way, of Jewish descend.

[15] Moritz Güdemann (1835 – 1918), Austrian rabbi and historian. By “head of the Jewish movement” the author refers to Güdemann’s leadership of the Orthodox Jews in Vienna. For a detailed description of Idelsohn’s encounter with Rabbi Güdemann, see Idelsohn’s article in the periodical Ha-herut, July 14, 1914, p. 2.

[16] A small neighborhood in today downtown Jerusalem, between Jaffa and Hanevi’im streets founded in 1896. Illustrious figures of the Yishuv lived there, most notably Itzhak Ben Zvi and his wife Rachel Yana’it Ben Zvi. In addition, three important Hebrew presses were located in this small bustling alley.

[17] According to Idelsohn’s own testimony he was first recruited as a clerk in the hospital and only later as “band-master in the trenches at Ghaza.” (Schleifer 1986a, 22)

[18] To what degree Idelsohn’s Army service detached him from his civil life remains uncertain. He is mentioned in the Hebrew press as a appearing in civil events during the war, apparently indicating that his recruitment was sporadic and confined to the performances and rehearsals of the Army’s band (in Gaza, as he testifies, or elsewhere). Idelsohn’s connection to the Turkish Army band however appears to have started long before the war. See the announcement in the Hebrew periodical Ha-habatzelet no. 65 (12 Adar 5669; March 5, 1909), p. 1: “The band of the Government’s Army will perform at the city’s garden in honor of the holyday of Purim on Monday at 3PM (9 Turkish time) before the festive meal. The program will include…Hebrew melodies [manginot ‘ivriyot] arranged by Abraham Zvi Idelsohn…” Further engagements of Idelsohn with the Ottoman Army’s band may be related to the appeals by the Jewish leader Albert-Abraham Antebi to the Governor of Jerusalem to have the band playing on Purim of 1913. Antebi based his appeal on the fact that the band also played for Christian and Muslim festivities in the city. See, Marcus, Amy D. Jerusalem 1913: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. New York: Viking, 2007, chapter 5. The Ottoman band marching through the streets of Jerusalem’s Old City in 1914 on its way to the invasion of Egypt can be seen in a rare footage in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3u1r4IPWVtI

[19] Shoshanah is most probably referring to the inn established by Yehoshua and Sarah Yellin, David Yellin’s parents, in 1871 on behalf of the travelers from Jaffa to Jerusalem. The inn was built on the remains of a crusader building. In 1905, a synagogue was built inside the compound. Next to the inn there is a famous spring. There are other springs in Motza Illit (Upper Motza). However, it makes sense that the Idelsohns would be guests of the Yellin family in Lower Motza, and the reference to the village of about two miles on the road down to Motza from Jerusalem further supports this hypothesis.

[20] The event took place in the afternoon of July 24, 1918, in the presence of General Allenby, the Mufti of Jerusalem and the guest of honor, Chaim Weizman, then head of the British Zionist movement, who gave the main speech. According to certain estimates, almost 6000 people attended the event although this figure appears to be exaggerated. It is known that at arrival of Weitzman the choir sang and that the event ended with the singing of “God Save the King” and “Hatikvah”. It may actually have been at this event that Idelsohn premiered the song “Hava nagila” in its choral version. In his testimony in the introduction to HOM IX (1932), he writes “In 1918 I needed a popular tune for a performance of my mixed choir in Jerusalem. My choice fell upon this tune which I arranged in four parts and for which I wrote a Hebrew text. The choir sang it and it apparently caught the imagination of the people, for the next day men and women were singing the song throughout Jerusalem.” Almost the same wording is used in his article, “Musical Characteristics of East-European Jewish Folk-songs,” The Musical Quarterly 18, no. 4 (1932), pp. 634-645. Although this testimony was written fourteen years after the 1918 eponymous event, it is rather curious that Idelsohn would refrain from naming specifically the nature of that “performance.” The few seconds of film footage and photos of this event that have survived do not show a choir. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7cjIaQ4NlJ8.

[21] This testimony contradicts or at least tempers speculations that Idelsohn’s sudden decision not to return to Palestine from his tour of 1921 was due to financial reasons. Compare Foreword to Idelsohn 1986, p. 13.

[22] See above note 12 on the Hebrew College for Teachers, known today as the David Yellin Seminar.

[23] The School was in fact the initiative of the Military Governor of Jerusalem, Brigadier General Roland Storrs, and the Jewish-British violinist Anton Tschaikov. The first director was Marie Itzhaki, and Idelsohn and the young British pianist Sydney Seal (1898-1959), who arrived to Palestine as a British officer, joined them. For details on this School see Hirschberg 1995, pp. 54-56. It is obvious that the name “Katshowski” is a gap of memory by the writer for “Tschaikov.”

[24] The Jewish settlement of Har Tuv (Ar. ‘Artuf) started as early as 1883. In 1895 the Hibat Tziyon movement from Bulgaria bought a substantial portion of the land. Immigrants from Bulgaria, among them the Bekhar family, were a prominent component of this agricultural settlement’s population. Only after 1909 the colony picked up. However, the settlement suffered from chronical financial instability and was devastated during the 1929 Arab revolt.

[25] These riots, known as the Nebi Musa riots, took place between April 4 and 7, 1920 in and around the Old City of Jerusalem. The riots coincided with and were named after the Nabi Musa festival, which took place on Easter Sunday. It followed rising tensions in Arab-Jewish relations shortly after the Battle of Tel Hai and a few days prior to the San Remo conference that decided the fate of the Middle East after World War I. It is uncertain where the Idelsohn family was living at this point, but apparently not in the Ezrat Israel neighborhood where they were located in 1914 because the Damascus Gate could not be easily seen from Ezrat Israel.

[26] Idelsohn produced in 1922 a series of 78rpm records titled “Hebräische-Palästin. Lieder” for the German label Polydor (Polydor H 70065-70091), one of the major international recording companies at the time. See: Lotz, Rainer E, and Axel Weggen. Discographie Der Judaica-Aufnahmen. Bonn, 2006. The identity of the performers in these recordings remained mostly unknown, thus the importance of this testimony.

[27] At the time of the recordings, the famed Ukrainian-born hazzan Salomo Pinkasowicz (1886-1951) was serving at the Adass Jisroel Synagogue of Berlin (dedicated in 1904). Around the same time he recorded several 78rpms of hazzanut for Polydor. See: http://www.yiddishmusic.jewniverse.info/pinkasowiczsalomo/index.html

[28] The name of Iosef Bornstein appears in one of the Idelsohn’s recordings as soloist. So far we could not locate information about this cantor.

[29] Jacob (Jakob) Dymont (1881-1956) was a choirmaster, conductor, composer of and instructor in Jewish liturgical music. Dymont was born in Kovno, Lithuania (then part of Russia) in 1881. He left for Germany when he was still a teen and studied music theory, languages, and Jewish music and music history. He received a master’s degree from the Royal Academy of Music in Berlin and in 1908 he became choirmaster at the Orthodox Adass Jisroel synagogue. He also accompanied cantor Pinkasowicz in his recording. His estate is at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, Manuscript Collection. MC 80/CJC. More on Dymont, see Nemtsov 2014.

[30] On the Cohon’s long-standing relations with Idelsohn see Judah Cohen 2010.

[31] In fact, Idelsohn’s appointment was as Professor of Liturgy.

[32] The first stroke, according to Idelsohn’s own testimony occurred in 1931. See Schleifer 1986a, p. 23 and our document,